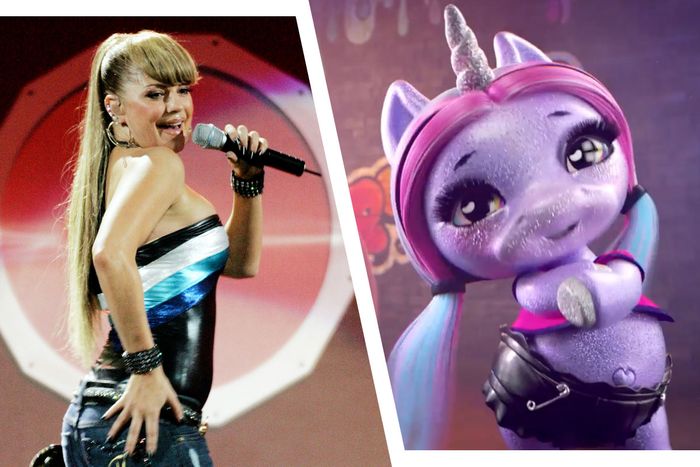

A Black Eyed Peas song is at the center of a lawsuit filed against the makers of a pooping unicorn doll for copyright infringement. There’s a lot packed into that sentence, so let’s break it down. When you press its belly, the Poopsie Slime Surprise toy dances to a song called “My Poops,” a bop that bears an uncanny resemblance to “My Humps,” by the Black Eyed Peas. The pooping unicorns also perform this song in an animated commercial. BMG, which owns the rights to “My Humps,” is suing for $10 million and the removal of the poop song’s video from the internet.

Oddly, this case — as well as another big case before the Supreme Court involving Andy Warhol and Prince — could have a big impact on the kind of music we get to hear and the kind of art we consume. Mark Joseph Stern covers the Supreme Court for Slate and explains how it’s all connected in the latest episode of Into It. Read an excerpt of that conversation below, or listen to the full episode of Into It wherever you get your podcasts.

Before we get into the legalese of it all, I have to ask point blank: Do you like the unicorn-poop song?

Like is not a strong enough word for it. I love the unicorn-poop song. I watched it ten times just to prepare for this recording, and I just became infatuated with it. It’s transformative, and I think it is deserving of the legal protection that its makers insist on. But, you know, I tend to err on the side of free speech. So it was inevitable that I was going to be on team Poopsie Slime Surprise here.

For those who haven’t been following this case, what is Poopsie Slime Surprise and what are its makers arguing?

Poopsie Slime Surprise is a line of unicorn dolls that excrete sparkling slime. That is their charm.

For that alone, they should win.

I totally agree. The ingenuity that went into making this doll … what will humans do next? But anyway, they’ve made these dolls. They want to market them, right? So they put out a video that’s designed to go viral. It features the Poopsie Slime Surprise dolls singing a song called “My Poops” that sounds a lot like “My Humps,” by the Black Eyed Peas. The record label that owns the rights to “My Humps” files a copyright lawsuit. They say, “This is clearly infringing on our copyright to ‘My Humps,’ the song by the Black Eyed Peas.” The lawyers for the label claim, and I’m quoting, that, “The Black Eyed Peas are arguably the most popular and recognized pop-musical group in the past 30 years.” Which I think is a contestable statement, but we’ll just go with that. Basically, they say that this is offensive to the artistic integrity of the Black Eyed Peas and “My Humps.”

The Black Eyed Peas are offensive to me as a person. Have you heard these songs?

I’m just telling you what the lawyers say here. I’m not stepping up for this label. They say that the fans deserve better than this, that the millions of folks around the world deserve to be able to listen to “My Humps” and not have that experience diluted by pooping unicorns. And they say that, basically, this company has just ripped a song, whose rights are fully protected, in order to sell a product, and that is the quintessential copyright violation. They’re asking for more than $10 million in damages plus an injunction that takes that video off the internet forever.

Are the unicorn folks just saying, “Well, actually we didn’t make ‘My Humps.’ We made ‘My Poops’?” ’Cause they do say, “My poop. My poop, my poop, my poop.”

They haven’t mounted a full-on defense here. But their basic argument is “Look, there’s copyright, of course. People get to hold the rights to their intellectual property and their art. But there’s this thing called fair use that is built into copyright law, really from the founding of this country, and it’s designed to kind of create a buffer for freedom of expression.” And fair use is pretty complicated, but at its heart, it says that, if you want to take an original work and transform it into something else by commenting on it, by making fun of it, by changing its meaning or its message, you are allowed to do that without paying money to the original copyright holder.

So who’s gonna win?

This is a really tough case. And one of the issues here is that, as much as I want to just stand up for the unicorn-poop folks, they have a problem, which is that, historically, and especially in Supreme Court precedent, this idea of transforming a piece of art through parody usually involves something that’s not so crassly commercial. The unicorn-doll people are trying to sell a product. They’re not making a song that they want to perform for the masses. They’re not making a short film that they want to submit to the Oscars. They just want to get these dolls in the hands of young children.

This leads to a very thorny question. Because, intuitively, that makes sense to me. Like, yeah, this is basically an ad, and that’s different from a traditional work of art, but at the same time, it’s 2023. All art is commercial on some level. Like, you make a parody song — you’re trying to sell downloads. You make a parody film — you’re trying to get people to buy the rights to it. This is not an easy line to draw, and this is a problem that’s gonna keep coming up in all of these cases.

The Supreme Court is currently deliberating on a case similar to this one. Same kind of issues at play, but it involves the estate of Andy Warhol and a photographer who took a classic photo of Prince. Can you tell me about that case?

So, this is an amazing case, and it’s another difficult one, because there are legitimate free-speech arguments on both sides. There’s this photographer named Lynn Goldsmith, who took this iconic photo of Prince. If you Google “Lynn Goldsmith, Prince,” you’ll see the picture.

In 1984, Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol to use that picture as the basis of a new work of art. Vanity Fair pays Goldsmith a paltry $400 to license the photograph as the basis of this painting, and Andy Warhol produces a work that I think most people would be very familiar with. It’s this silk-screen painting of Prince that has a kind of hollowed-out feeling. It’s very flat. His face looks masklike. It is different from the original picture, but obviously based on it. So Vanity Fair puts that on its cover. Andy Warhol actually goes on to create a bunch more works based on that picture, and nobody ever pays Goldsmith any more money. The only money she ever got was the $400 from Vanity Fair up front. In 2016, Prince died. Vanity Fair puts that Andy Warhol piece on the cover of its magazine as a tribute to Prince, and Lynn Goldsmith comes out of the woodwork and says, “Hey, I licensed my photograph for this one painting this one time, and you’re putting it on the cover of your magazine all these years later to try to sell copies. You owe me money.” The Andy Warhol estate goes, “Oh, we have a problem here.” Vanity Fair is caught in the middle. The Andy Warhol estate then goes to court and says, “You know what, Lynn Goldsmith? We’re gonna sue you.”

Wait, wait, wait. They sued Lynn?

They say, “We need this court to tell the world that we own the rights to these works, that all these paintings and drawings are ours, and that you do not have any copyright claim over this.” So Lynn is the one who gets sued, and that is how this case makes its way up to SCOTUS.

You told me before that this was going to be an “atomic bomb in the art world.” Why?

Both sides have a whole lot to lose in this case. Start with the photographers. Every photographer you’ve ever heard of has said, “This is an existential threat to our profession, because photographers need to be able to get paid for their work, and if you can just take a picture and touch it up and make it look a little different and say, ‘Oh, I don’t owe anybody anything,’ then photographers are all gonna be penniless and out on the street, and their profession will go away.”

On the other side, you’ve got all of these artists, all of these museums, all of these lawyers who do art law. You’ve got the Art Institute of Chicago, you’ve got the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation saying, “If this is really infringement, then we are absolutely terrified that we are gonna get slapped with suit after suit based on what is hanging on our walls.” Because they have a lot of modern and postmodern art, and the reality is that a lot of that stuff is based on previous works by previous artists.

What was the mood like in the room during oral arguments? Can you make any predictions about how the justices will rule?

The mood was alternately goofy and tense. The lawyers there arguing for both sides did a really good job, and the justices were seemingly groping toward a solution in good faith without any partisan violence. And I think that’s important to note, because in most of the cases I cover, there’s some kind of political angle — whether we’re talking about elections or race or even free speech. A lot of that stuff does play into politics. This is not so clearly political. This is a case about what constitutes art and when a new kind of art gains its own independent existence.

But then you started hearing concerns about technology. How the rise of phones, AI, and cameras that everybody has and can use to manipulate pictures and so much more — how that could affect the analysis here, because the Court hasn’t considered one of these cases in a long time. People didn’t even have flip phones the last time the Court took up a case like this. Now they’re having to deal with the fact that you don’t have to be Andy Warhol to transform a photograph. You have AI that makes you look like a sexy villain or like a buff superhero in 100 different photos.

We’ve seen this struggle play out in court cases for as long as people have owned art or had ideas about art. Is it really fundamentally different now with AI and the speed at which computers can generate, say, 1,000 prints of Warhols in two minutes?

Yeah, I really think this is a challenge to this entire area of law, because the way it was considered before was based on the fact that people really put their blood, sweat, and tears into transforming these works. There’s a famous case where there was a parody of the song “Pretty Woman,” the Roy Orbison song. This group called 2 Live Crew decided to do their own version.

I was hoping you’d get to 2 Live Crew.

That goes up to the Supreme Court. The question is, is that fair use? Is it transformative? And the Court says yes. And one of the big reasons is because they say, “Well, look, 2 Live Crew put a lot of thought and care into devising this parody of the original and really made sure to kind of take the ideas that were expressed in the original and turn them on their head.” That was back in the ’90s. Today, I can go on ChatGPT and ask it to write 100 parodies of “Pretty Woman” and they all might be better than the first one. I really don’t know whether it’s still transformative when I outsource the work to a robot, and that’s one of the big issues that this Court has to decide.

How much of all of the music industry stuff, the poop stuff, the Warhol-print stuff — how much does the whole public domain of it all play into this? From my understanding, once anything is 100 years old, anybody can do whatever they wanna do with it anyway, right?

It’s a great question, and I actually think that the shrinking of the public domain has led to a lot of the disorders and pathologies that we see in copyright law today. Back when the founders wrote the Constitution, they envisioned a very large and robust public domain and did not expect copyrights to last for very long. The whole point of copyrights was to protect your work for a short amount of time, so you could get some money off of it, then release it into the wild — like a young whale who has been rehabilitated to go find its home and family and live its own life. Thomas Jefferson would not have wanted the Black Eyed Peas’ label to sue Poopsie Slime Surprise. I promise you that.

The problem is that when people own the rights to their work, they make a lot of money off of it, and what happens in the United States when you make money? You spend it on elections and on politicians. So what has happened over the centuries is that corporations that own a ton of copyrights have periodically gone to Congress and asked Congress to extend the length of copyrights by decades and decades and decades. And that is how we’re in this position today, when stuff is only entering the public domain a century after it has been published.

So what would change for me as a consumer of entertainment based on the Supreme Court’s ruling? Is this just gonna be an ongoing fight?

I think this fight’s gonna go on as long as there’s a lot of money on both sides. It’s really notable that here, both Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation were able to hire two of the most prominent and expensive Supreme Court litigators to argue this case. There is big money here, and it is because copyrights still produces a whole lot of moola for the people who own them. What I would say is that, in the end, Congress really has to come in here and set some ground rules. And I know that’s a big LOL ,because Congress doesn’t do anything.

Ha! LOL.

And that is generally true, but when you’re dealing with stuff like AI, where somebody can take a copyrighted work and transform it 100 times over in a second and call that fair use, the courts are not equipped to deal with that — just as they aren’t equipped to decide what’s art and what’s not. And that’s sort of the fundamental question in this case: Is the Andy Warhol work a different piece of art? Or is it just a crass copy? The courts have long said, “We don’t wanna do that. We are bad art critics. We do not have good taste in this stuff.” They might have personal taste, but they understand that they cannot be the tastemakers for the country, and I think the task really does fall on Congress to decide how you write a new copyright law that respects the rights of people who own this intellectual property while allowing creators, podcast hosts, painters, interesting and thoughtful people to work off that original and develop something new without getting slapped with a multimillion-dollar lawsuit.

When should we expect to know something about the Warhol case from SCOTUS?

So, this was one of the first cases that the Court heard this term back in October, and I think a decision is likely to come down probably by April — if not, by May. The fact that we haven’t gotten a decision yet suggests that the Court is divided. If it takes this long, it usually means somebody’s got the majority, somebody’s writing a dissent. There’s a chance that the Court could divide so badly that they don’t end up really solving anything. So as much as the entire artistic industry just wants a clear answer here, the Court might not give one, and that means we will all be in the same place: trying to figure out what is original art, what is copyright infringement, and what falls in the vast chasm in between.

For devoted pop-culture junkies hearing this conversation, saying to themselves, “Well, I wanna know how to be on the right side of this,” how should they consume art differently or better knowing that all of these fights are happening?

I mean, I fall in the same bucket as you, where I think more freedom is better. And one of the defining moments here for me was when Olivia Rodrigo’s album came out, and obviously I loved it. (You know, I am homosexual.) When that album came out and started making money, the rights holders started coming out of the bushes saying, “Hey, this song sounds a lot like a Taylor Swift song. This song sounds a lot like a Paramore song.” And you better lay down some money and give some credit if you want these songs to stay on the radio. And I think that was total b.s.

Olivia Rodrigo was not doing anything different from Michelangelo or Leonardo da Vinci, honestly. Those guys were looking around, seeing what other people did at the time in Florence and Rome and wherever, and copying some of it. The Renaissance artists, from top to bottom, were absolutely incorporating other people’s ideas and other people’s work, and that has held true throughout all of history. And this idea that just because the bridge of one particular song kind of sounds like the bridge of another, that if you put them side by side, you sort of hear the resemblance — that, to me, should not be a copyright violation. That is the quintessential example of somebody transforming somebody else’s idea into something new and fun and expanding the universe of art that everybody gets to enjoy.

You gotta think of the bigger picture, which is that we live in 2023. Everything that’s been done will be done again. Everything that can be done has already been done. We’re building off each other’s ideas, and we should be letting people come up with interesting new ways to express stuff — even if they’re building off the works of their ancestors. Describing Paramore as an ancestor makes me feel very old, but Sam, I think it’s the truth.

What I hear you saying is “Justice for Olivia Rodrigo. Justice for Warhol. Justice for the ‘My Poops’ Unicorns. Let it all be free.”

I could not agree more.

This interview had been edited and condensed.