There’s a seemingly inconsequential moment toward the end of Margo Price’s memoir, Maybe We’ll Make It, that sums up the 250 pages before it. It’s 2015 and the singer-songwriter is determined to spend her day off from a stressful tour poolside, with a bottle of tequila, at a hotel too nice for her struggling band to actually stay at. The group protests sneaking in before her fiddle player, Kristin Weber, speaks up. “Don’t y’all get it?” she asks. “Margo is going to do what Margo wants, and that’s just that.”

By that point in the book, you get it. Maybe We’ll Make It, released this past September, focuses on Price’s career before her mid-2010s breakout, an era driven by her headstrong insistence on being a musician her way or not at all. That meant writing her own songs with her guitarist husband, Jeremy Ivey; struggling through DIY tours; and turning down anyone who wanted to polish up her retro-tinged, forthright songs. Just pages after that (successful) pool outing, her attitude finally pays off: Price — more than a decade and multiple bands into her career — signs to Jack White’s Third Man Records and releases her successful solo debut, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, before earning a performance slot on Saturday Night Live.

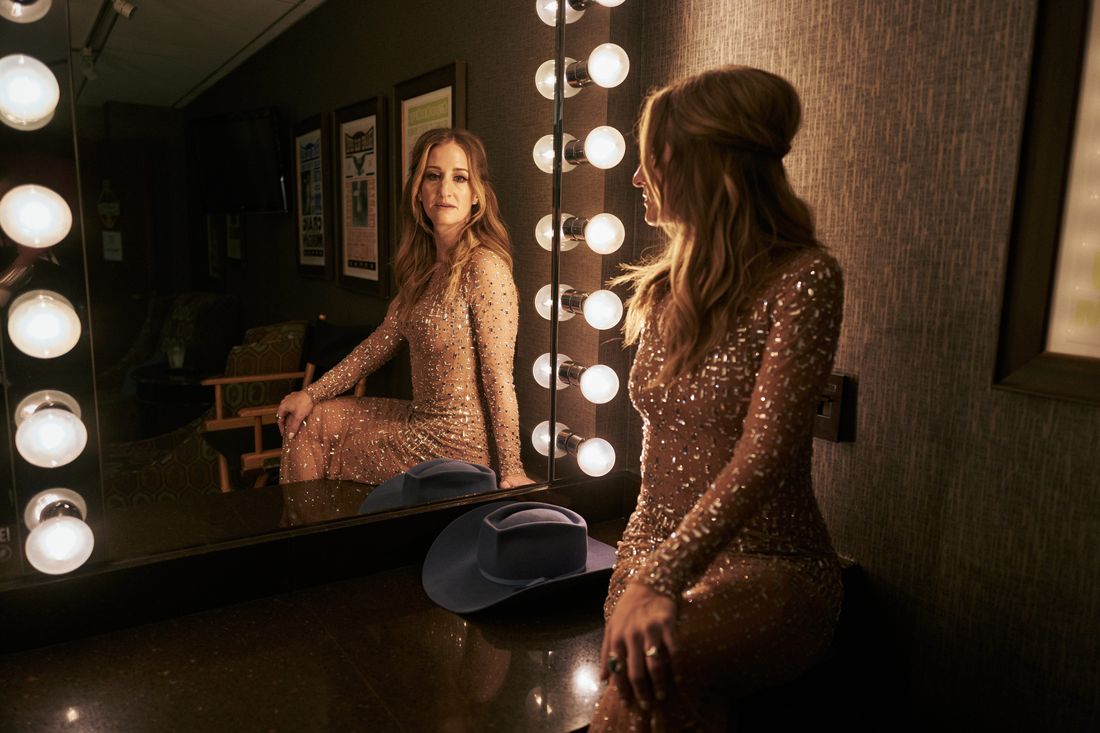

Years later, Price doesn’t drink or need to sneak into hotels, but she’s just as stubborn. She also barely makes country music anymore. Her new album, Strays, is her most experimental and incongruous collection of songs yet, even after she veered into classic rock on 2020’s That’s How Rumors Get Started. The new record spans psychedelic rock, dark epic ballads, and light-on-its-feet jangle pop while centering on Price’s confidence, which has only clarified over time. She puts it well on the album’s Joplin-channeling first single, “Been to the Mountain”: “I just know who I’m not, and that’s all right with me.”

Price has had even more time to think about her identity when I meet her for lunch one unusually warm fall afternoon in Chicago, weeks into the tour for Make It. She’s been enjoying the alone time that promoting the book has afforded her compared to touring with her band; it’s often just her driving her truck between cities, listening to an album or a podcast. While she is hoping the trip will pay off by recapturing some of the momentum of her breakout record, she’s not ready to sacrifice her integrity along the way. “I’ve had a lot of opportunities to do other things that probably would have made me more successful,” Price tells me. “I see peers of mine that end up making the same records over and over that seem like they’re just chasing the success of it all. And I’m like, I’m just chasing the song.”

From the epilogue of the book, it seems like you’ve been thinking about slowing down a bit, and now you’re promoting both a book and album.

It’s this double-edged sword where when I’m home, I want to be working; when I’m working, I want to be home. And trying to balance the mom life with the rock-star life — and now the author life has been really a challenge. I have friends hitting me up, and I’m like, “I’m sorry. I’m never going to be able to see you again because I’m just too fucking busy.” Really, I had just gotten my career off the ground when I found myself pregnant and then COVID hit. So I wanted to be able to have another renaissance of just getting my name back out there. I knew I was going to have to do something big.

It was funny to read in the book about all your influences who are not country — and be reminded that your career has snaked through these different genres — and then to listen to the new album that’s not quite a country album either. People were talking about your last record, That’s How Rumors Get Started, as more of a detour. But with Strays, it seems like this is —

This is more. How many wrong left turns can I take in my career? I know a lot of people just want country music from me. And while on this album we snuck in some pedal steel, and it still is my band playing live in a room, and there’s lots of acoustic instruments, it’s hard to describe what genre it is. I really do feel like it is a bit genreless, but I still feel like it’s me and it’s focused on the song. That’s all that I care about, is that a song’s good. Do they connect to me? And do they connect to other people? We’ll see.

How did you figure out what you wanted this one to sound like?

Well, psilocybin has been very good to me lately. Getting into the psychedelic nature of this album was where I wanted to venture. That’s How Rumors Get Started felt like, Yeah, I want to make a rock-and-roll record. That’s what I told Sturgill. But with this one, it was listening to a lot of different things while we were on mushrooms. And then, the next day, we would wake up sober and then we would write. When I started writing it, I was still drinking. Then through it, a lot of things have changed, but there was definitely a lot of weed smoked, a lot of mushrooms eaten, several other things sprinkled in there on top of it.

The band has really shaped how this album turned out as well. A lot of times when me and Jeremy would be playing things on an acoustic guitar, it wouldn’t really fully form until we got into the studio. The song “County Road,” that came together in the studio, and that was really transformed when my rhythm section got a hold of it.

There are parts of this album that sound darker than anything else you’ve done. “County Road” is almost southern gothic.

Love that. I wanted the album to be like a psychedelic trip, where you go into dark things sometimes. You’re like, Do I want to look in the mirror? Do I want to see what’s there? But that was just a song that really needed to be written. We all lost this really good friend of ours a few years ago. His name was Ben Eyestone, and he was a drummer. He was having a lot of health problems and then he died very, very suddenly from colon cancer. He never had a car, and he was always borrowing all of our cars and borrowing my bass player’s car ’cause they lived together. It was a song about him finally getting some wheels when he got to Heaven. And also, it was like he got out before the world kind of turned to shit. So that song means a lot to us collectively as a group. You want to connect to the song emotionally when you’re singing it, but it’s one that if I think too hard about it, I’ll start crying onstage.

Were you writing this as you were finishing the book, or had you finished the book and then started on the album?

They were going on at the same time. I started writing the book in 2018. It took about four and a half years to complete. Then I started writing this record in 2020, and the editing process of the book was still going on. So the book has a couple chapters that ended up being song titles.

So those started as the chapter titles?

Both, I guess. Some of them, I went back and ended up naming the chapters after songs because I couldn’t figure out what chapters should be called. When I first wrote the book, it was just 500 pages of word vomit, like Kerouac scrawl. I didn’t even know it was 500 pages. Later, I went back, and a couple of [chapters], I was like, Hey, you know what? ’Cause a lot of the album, too, is about my past or places we’ve been, things we’ve been through. It’s funny how they mirror each other.

It was interesting to read about some of these early, more protest-oriented songs that you were making and then see that coming back around on songs like “Been to the Mountain,” where you’re singing about capitalism and climate change.

Yeah, I’m really proud of that song, and I’m so stoked that my label wanted to put it out as the first thing. I just thought, This five-and-a-half-minute song with a weird fucking poem in the middle — are people going to get it? But we played a lot of these songs out, like, to test-drive them. A lot of times, it’s hard to get fans to react to a song that they’ve never heard, but “County Road” and “Light Me Up” and “Been to the Mountain” got such a visceral reaction from the crowd. We’re like, Okay, those are definitely going on the record.

Did you find processing things through prose different from writing songs?

It’s going to sound really cheesy, but when you’re writing songs, even if you’re writing things that are about yourself, you can still be ambiguous and you can still hide things in metaphors. You don’t have to be completely direct with your audience, like, Is this about me? Is this about someone else? But with writing the book, I processed a lot of things that I had been hung up on.

Also, it’s just so much more time-consuming to write a book, and I had no idea that it was going to take that long. I didn’t even know that people used ghostwriters to write books. But I definitely took the hard way. Songwriting, sometimes the song comes lightning fast. But, man, the book — I almost couldn’t multitask. Sometimes I would put the book down for months in the editing process and then I would write a couple songs, because I couldn’t do both at the same time. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into.

The ending of the book got me curious about how being on Third Man impacted the way you saw yourself as an artist. I remember around that time, it was like, “first country artist on the label,” but also to be an artist in Nashville not on a country label.

I think it gave me free rein to do whatever I want. Jack is one of my biggest musical inspirations, even before I ever had that opportunity to be on their label. The fact that he can play country, he can play rock and roll — he can do all those things and it’s all based around the blues. I am so grateful for every single person that turned me down because if I just would’ve been on whatever Americana indie label in Nashville with everybody else, I feel like that just made me stand out. I don’t think that I would’ve got Saturday Night Live or all those things.

I am so grateful to Third Man for believing in what I was doing. A lot of people, when they’d come out to the shows, they’d be like, “I’ve never listened to country music — I’ve never liked it before — but I really like you.” And when people come to our live show, they’re getting much more than just a country show. They always were, even from the beginning. We were trying to sneak psychedelic jams in there; we were trying to put in funk and blues and soul and all those things. Now it’s just on the records.

It was cool to see Mike Campbell of the Heartbreakers on the new album. What was it like to get him on “Light Me Up”?

It was wild. All American Made I dedicated to Tom Petty and just was devastated that he passed right before it came out. So my label wanted me to try writing with some people for this record other than my husband. I’m very stubborn and set in my ways. But my manager said, “Hey, why don’t you write with Mike Campbell?” And I was like, “Yeah, I’d love to do that, but he doesn’t have time to write with us.” We hit him up, and he had only written with Tom and Chris Stapleton recently. He gave us so much good songwriting advice — just really how to write good hooks and trim the fat and make things concise. And we’ve become really, really close with him.

So he came in, he laid down that lead on that song — it was his first take. [Laughs.] He’s like, “Oh, you want me to bow-ditty, bow-ditty?” And we were like, “What?” He’s like, “You know [imitates guitar riff].” Yeah, he was being hilarious. I co-wrote a couple other songs with him that are hopefully going to come out, and he sang on some of them. Benmont had played on my previous record, but Mike doesn’t really collaborate with that many people, so that just meant so much. Also, Benmont had just recorded a record at Jonathan Wilson’s, so his grand piano and the Heartbreakers’ organ was in there. So that’s what you hear all over the album. It’s really special because there’s no other organ that sounds like that one.

I did want to ask you about Loretta Lynn, of course, whom you got to know and work with over the years. How were you able to make sense of her dying on the same day your book came out?

Oh my God. It was a really hard day. And, you know, she lived a really long life and everything. But I was in shock. I had a bunch of stuff planned for that day, but honestly I couldn’t do it. I just lay on my bed and cried for a few hours. [Pauses.] It was almost just Kismet. It was like, Well, of course she would die today. [Laughs.] I’m still trying to process it.

Have there been certain memories of her that you’ve found yourself returning to?

So many memories have been flooding back. The very first time that I met her, we were backstage and her daughter brought me back. I was shaking and was so nervous. And she’s like, “Mom, I want you to meet Margo. Y’all are so similar because you both kind of write similar songs and you’re both Aries.” Our birthdays are one day apart. We’re both color-blind, which is very odd. Then she was like, “And, you know, you and Margo share something in common that’s pretty tough: You both have lost your sons.” And Loretta just looks at her and she’s like, “Now shut the hell up, Patsy! Who would want to talk about something like that right now?!” [Laughs.] And I just started laughing so hard. It could have went dark, but she just made it so — we just laughed.

I remember, too, when she called me out of the blue one day, because we were doing a tribute at Bridgestone Arena. Jack and I ended up singing “Portland, Oregon” together, and I sang “One’s on the Way” when I was ten months pregnant. I was so pregnant. She calls me on the phone, and she’s like, “Hey, I’m doing a birthday celebration, and I want to plan it myself. I know after I die, they’re going to do a tribute, but I want to get all the people that I actually really like to do it, so I wanted to ask you if you would be a part of it.” And I was like, “Yeah, of course.”

I was on the set that day for my music video for “All American Made.” And I was pregnant. I was scared to death that my whole career was going to be over because I had just got going and everything. She was like, “Patsy said you were thinking about having another baby.” Because I’d seen [Patsy] a couple weeks prior for a thing, and I was like, “Did you ever resent your mom for being away?” And she’s like, “No! It was just how it was. My mom was Loretta Lynn.” She’s like, “Why? Are you thinking about having another kid?” I was like, “Maybe.” So when Loretta calls me, she’s like, “Well, I think you should. You should have five more babies. Don’t even worry about it. Your fans are going to love you no matter what.” And she goes, “And if you do, I give you my blessing to use Lynn as a middle name, because it works for a girl or a boy.” So my daughter is named after Loretta.

It’s striking to get to the end of the book and you’re in this moment where you’re playing SNL and nominated for Grammys — it’s this version of success that a lot of people want — and to see what you’ve done since then, which I still think has been very successful but has been about charting your own path. Has what you consider being successful changed?

I thought back during that time when I was so depressed, and when I was struggling with the drinking and everything, it was because I wasn’t successful. But then I realized that there’s always a comedown after doing something really big. Like playing SNL, the next day or a few days after, you’re going to feel low again. And I just thought that once my music took off, all my problems would be solved. And then I thought again, once I quit drinking, Now I’m never going to be in a bad mood again because I’m not struggling with this. Lo and behold, I still get really down sometimes.

I think success, for me, is being able to just be happy with what I’ve done so far, be happy with the art that I’m making, not get caught up in Do I have a Grammy? Is the book going to be on the New York Times best-seller list? All those things. Because the second I start getting lost in that, it’s so counterintuitive. That’s not why I picked up the guitar in the first place. And I always have to go back and remind myself why I did. It’s just because I love to sing and I love to write songs, so I have to keep going back to that. The second I start feeling like that, I’m like, It’s time to write another song.

I had read you talking about turning in the book and your editor mentioning that it felt like whiskey was a character. As you were writing over the years, how were you thinking about the way your drinking was popping up as a through-line?

Well, like I said, there was no ending to what I was writing. That was the hardest thing for me. When my editor, Naomi Huffman, said that to me, I was in one of my lower points where I was really, really leaning on the booze. It was hard for me to hear that. And when I looked back at a lot of the points I was talking about the drinking, it wasn’t framed in this, like, “That was really stupid. That was really dangerous.”

I kind of knew that I was getting ready to give it up, but in that process I wanted to drink as much as I could so I would not want it. So I kept drinking through November and December [2020] and then finally I took this big mushroom trip and went into it with that intention and started having all these epiphanies. I’m always careful to say I’m not sober but I’m alcohol free. And, of course, it wasn’t just, like, Oh, I ate the mushroom and then that was it. I went out; I bought a bunch of books. I tried to really take some steps to actually make it happen. There were so many times I was like, I’m done drinking, I cannot live like this anymore, thinking about checking myself into rehab — all the things. And then it would just creep back in slowly. So, yeah, I think the book was a big part of therapy. I only started therapy a year ago, so I really think writing and eating the mushrooms, that was a big eye-opener.

It’s great to have the book end on that.

The first draft of the book was very, very different. I wasn’t lying, but I was leaving things out. Even in the middle of writing the book over the past four years, I have been debating all these things. Like, Would my career go better if I went and got my lips injected with this shit? I’ve got to go get a nose job because I’m so fucking ugly, and that’s the only thing that’s holding me back. Finally I came to this breaking point with all that. I was like, I look different. I sound different. This is who I am, and I’m going to actually talk about how insecure I am. Because from the outside, everybody thinks — it’s always the headline “Country Badass” and this and that. And I’m like, No. I struggle very much with my self-image.

I knew for so long I really would probably be better off if I could just quit the booze. But I was so worried about people thinking I wasn’t cool, about people thinking, Oh my God, I didn’t know she was struggling. I didn’t know she was an alcoholic. And obviously I did really struggle with it, but I have totally given up on caring what anybody thinks about me. And I feel, like — everybody else drinks, so it’s like, Hey, I’m actually going against the grain.

It’s been a theme in this conversation.

Right. Going against the grain, doing something different and it’s like, Shit.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.