The Military Weapon That Has Become a Musical Touchstone in Ukraine

These are the viral songs of a country under siege.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Turkish-made aerial drones armed with laser-guided missiles have, in the past two weeks, helped Ukraine slow Russia’s invasion. Known as Bayraktar TB2s, the drones are not just a piece of military equipment anymore. They are symbols of Ukrainian resistance—and the inspiration for a very catchy song.

A track titled “Bayraktar,” of indeterminate origin, has been receiving hundreds of thousands of plays online, and is in rotation on Ukrainian radio. Over a simple beat, a gravelly voice insults Russian President Vladmir Putin’s forces—their equipment, their mission, and the soup they consume in their possibly doomed tanks. Roughly translated into English, here is how one verse goes:

They wanted to invade us with force

And we took offense at these orcs

Russian bandits are made into ghosts by

Bayraktar!

“Ukrainians are very funny—there’s this deep, dark humor,” Adriana Helbig, the music-department chair at the University of Pittsburgh and an expert on the country’s culture, told me on Tuesday. Listening to Ukrainian broadcasters over the past few days, she has been struck by a witty, even upbeat, tone amid the ongoing destruction. “They’re like, We’ll be back to our regular programming as soon as we kill off our invaders.”

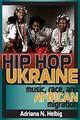

I had reached out to Helbig to learn about the sound of Ukraine, both during this invasion and before it. Last year, viewers around the world were mesmerized by the country’s entry for the Eurovision Song Contest: an intense techno track about environmental catastrophe, featuring folk melodies from the Chernobyl region. In 2004, the Eurovision winner was a Ukrainian pop star who went on to serve in the country’s Parliament. Helbig has written a book about Ukrainian hip-hop, the genre that cheered on the 2004–05 Orange Revolution and has received global attention in recent years. All of this musical activity would seem to plainly undermine Putin’s claim that the country has no culture of its own.

Tune in to Radio Bayraktar—a channel that just launched on Radioplayer, an app that has been endorsed by the Ukrainian information ministry—and you hear rollicking, war-ready pop that shows off Ukraine’s particular influences. Rock and roll blended with electronica and hip-hop dominates, flavored by bits of folk melodies and instrumentation. When I listened this week, I was jolted by a ska track commanding “Military run!” (The band, Mandry, had just released the song in response to the invasion.) Later I heard the “Bayraktar” tune, as well as an achingly powerful rendition of the Ukrainian national anthem.

The anthem has become the signature sound of Ukrainian resistance: played by soldiers at blast craters, sung abroad in acts of solidarity, and reportedly employed by hackers jamming Russian communications. Based on the 19th-century poem “Ukraine Is Not Dead Yet,” the song’s lyrics—“Our enemies will die, like morning dew in the sun / Brothers, we will rule in our own land”—certainly suit the situation. Helbig thinks the war is even helping to popularize the anthem throughout the young, sprawling nation. Historically, “Ukraine doesn’t do rah-rah-rah patriotism,” she said. “They’re not flag wavers—they have a ‘Do what you want; leave me alone’ kind of attitude.” But “Putin has created his worst-case scenario. He’s unifying Ukraine.”

Amid dire conditions and often-limited internet access, the music arising from the war front itself is bespoke and singular. A Ukrainian girl singing “Let It Go” in Russian in a Kyiv bunker attracted international acclaim, including from the Frozen voice actor Idina Menzel. Two new soldiers got married at a military checkpoint with lively musical accompaniment, to much media attention. An online following has sprung up around an apparent Ukrainian soldier who performs patriotic songs in a smooth, dignified croon. “If I die in the field, don’t cry after me,” he sang in Ukrainian from behind the wheel of his car. “I will give it all, for our cherished mother Ukraine!”

@yuragorodetskiy #українапонадусе💙💛 #українськийтікток #одесса #україна🇺🇦 #зсу🇺🇦 ♬ оригинальный звук - yuragorodetskiy

Many of the songs being sung right now reflect Ukraine’s long struggle for autonomy from Russia. Helbig said she has been moved by clips of Taras Kompanichenko, a well-known folk musician who has taken to singing while wearing fatigues. Kompanichenko’s lute-like instrument, known as a kobza, was widely played for hundreds of years in Ukraine—until the 1930s, when Soviets are believed to have murdered many of the country’s traveling minstrels in an attempt to purge the culture. A monument to those persecuted musicians stands in Kharkiv, one of the cities now undergoing heavy shelling.

In the past 20 years, as Ukraine democratized and developed, a new generation of artists such as Kompanichenko amplified the country’s once-suppressed music traditions. Now, on Facebook, the world can watch him sing of taking up arms on behalf of women and children—old poetry, made painfully new again.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.