Earl Simmons, better known to the world as DMX, had one of the most wonderfully chosen names in the history of rap. X, who died on Friday after suffering a cardiac arrest a week earlier, took his moniker from the Oberheim DMX drum machine, an instrument he’d fallen in love with during a childhood stint at a boys’ home. The Oberheim DMX is the drum sound heard on Run-D.M.C.’s “Sucker M.C.’s” and “It’s Like That,” along with countless other golden-age boom-bap classics, and it’s a perfect metaphor for the rapper who took it as his name: rugged, percussive, hip-hop to the very core.

DMX dominated hip-hop in the late 1990s and early 2000s in clubs, on rap radio, and on the album charts. He came into stardom later than usual—he turned 28 in 1998, his breakout year—which meant that he arrived fully formed and bursting with music. He was the first artist in history to see his first five LPs debut atop the Billboard album charts; the two albums that DMX released in 1998 alone, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot and Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood (X had a way with titles), sold more than seven million copies between them. He was inimitable in the literal sense; I have recently seen him described as “influential,” which is certainly true, but from a strictly musical standpoint, I can’t think of another MC who’s successfully attempted to rap like DMX.

X’s music often displayed startling vulnerability and emotional depth, but the rawness of his subject matter and delivery could sometimes overshadow what a fantastic craftsman he was. He wasn’t a wordy virtuoso in the mode of say, Eminem, whose own meteoric rise followed X’s by a year. But DMX was a master of rhythm, tonality, and sonic drama; many of his best performances felt conversational, even improvisational, a quality that attested to his exquisite command of his instrument. He was a master of space and breath control—in DMX’s music, the silences were often as dramatic as the sounds. He rapped like a great drummer, or a virtuoso of the machine he’d named himself after.

Before he became one of the biggest stars in the world, DMX had been kicking around the music industry since the 1980s, and in 1991 had scored a feature in The Source’s vaunted “Unsigned Hype” column. That notice landed him a major-label contract with Columbia subsidiary Ruffhouse; Ruffhouse put out a couple singles that flopped and then dropped him. He floated around the edges of New York hip-hop throughout the mid-1990s, recording some now-legendary guest appearances on tracks like Mic Geronimo’s “Time to Build” (alongside a then-unknown Jay-Z) and LL Cool J’s “4, 3, 2, 1.”

Buzz from those turns led to a contract with Def Jam, who released X’s first proper hit in early 1998, the Dame Grease–produced “Get at Me Dog.” “Get at Me Dog” is an impelling and incendiary piece of music, like four minutes of a bomb going off. It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot arrived a few months later, in May; the album debuted at No. 1 and sold 4 million copies. By now in his late 20s, Earl Simmons was suddenly the hottest star in hip-hop. The follow-up, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, was rushed out in time for Christmas (you can hear that story on a recent episode of my colleague Chris Molanphy’s Hit Parade podcast) and topped the charts as well.

To my ears, X’s signature work will always be the epochal “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem,” which peaked at No. 93 on the Hot 100 but absolutely saturated the summer of 1998. In many ways, it’s remarkably strange, with X careening between barks, shouts, and mutters over a mad-scientist masterpiece of a track by Swizz Beatz. The production is lean and relentless, composed primarily of a pounding drum loop and a spiky, piercing synthesizer riff. It’s a radical and totally unique work; “Something new” are the first words out of X’s mouth, and that’s an understatement. No one has ever made a piece of music more perfectly calibrated to bang out of Jeeps.

X was absurdly prolific in this period. Along with the albums—three in a two-year span—he turned in show-stopping guest features on tracks like the Lox’s “Money, Power & Respect,” Cam’ron’s “Pull It,” and Jay-Z’s “Money, Cash, Hoes.” Some of X’s most indelible work came on tracks with other artists, which only enhanced the singularity of his presence. He’s hard to write about because words on the page can’t begin to capture the sonic power of his art. A line like “what you don’t know is gonna get you fucked up” reads as pretty straightforward, but hear it in X’s gruff, punching snarl, and it stops you in your tracks. One of my favorite DMX performances is in “N—-z Done Started Something,” the last track on It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot that features the Lox and Mase. X takes the last verse and just murders the track, a reminder that he could be a phenomenal lyrical technician when occasion called for it: “Now who gon’ tell your mother her baby’s under a cover / In the morgue, stiff as a log, sniffed out by the dogs?”

Earl Simmons’ dazzling talent was never his whole story. He lived a difficult life, a fact of which he made no secret. The story of his childhood is heartbreaking—he was in and out of group homes and various forms of incarceration, wandering the streets of Yonkers and befriending stray dogs to escape his abusive mother. In the 21st century, he continued to battle his demons and face legal and personal troubles, sometimes finding himself in the crosshairs of the most leering purveyors of tabloid media.

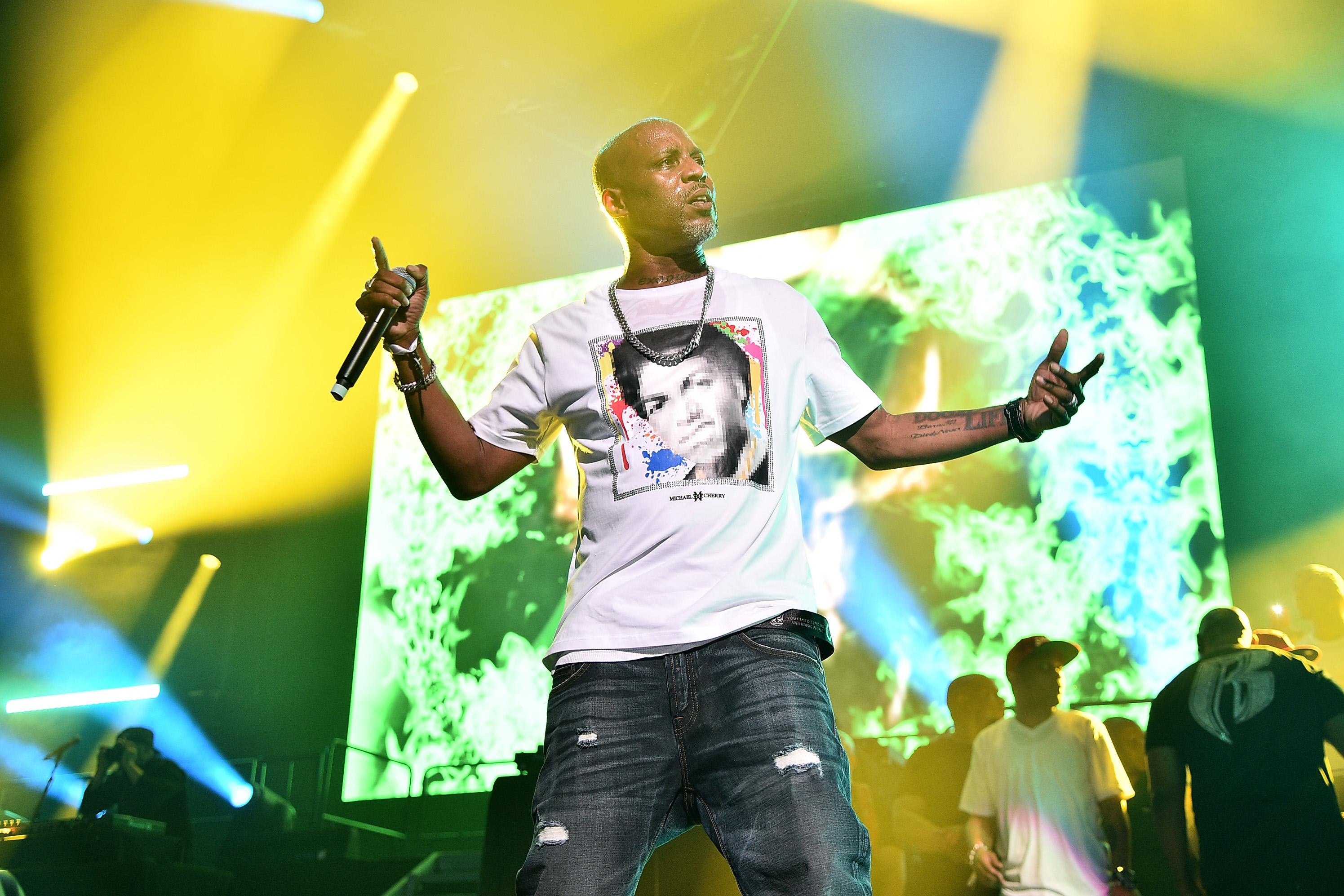

But that shouldn’t be how he is remembered, and it won’t be. I saw why firsthand, when I was lucky enough to see DMX in concert at the height of his powers, right around the turn of the century. The very best live hip-hop shows have a transportive quality to them: Precious few rap fans can say that they’ve been with the music since its subcultural beginnings in the South Bronx of the 1970s, but a great live show can feel like a connection to those earliest years of park jams and sweaty rec rooms and stairwell cyphers, all joy and invention and audacious charisma. Rakim’s famous adage that “M.C. means move the crowd” sounds corny until you experience someone actually doing it, and then it’s like an out-of-body experience. I saw DMX work thousands of people into a state of unfathomable energy and ecstasy, the kind of show that leaves you gasping for breath and unable to sleep. I’ll never forget that night, and neither will anyone else who was there.