Being a writer about music who happens to share a name with one of the Beach Boys brings lots of minor inconveniences, mainly in googleability. But the oddest result came on March 27 this year, when suddenly, in the early weeks of quarantine, I heard Bob Dylan sing my name. It was the day he released his longest song ever (in a career that had seen him trample the fences of pop brevity as far back as 1965’s 11-minute “Desolation Row”), “Murder Most Foul,” the first track put out from this week’s remarkable new album, Rough and Rowdy Ways. It’s a nearly 17-minute exegesis on the JFK assassination and from there into a seemingly infinite cascade of American cultural references, like an answer song to Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire” that snorts, “What? Of course we did.”

It happens at 11 minutes and 45 seconds, where Dylan creaks, “Play it for Carl Wilson, too/ Looking far, far away down Gower Avenue.” I quickly realized it was a nod to the Beach Boy as a harmony vocalist on one of Dylan’s favorite songs, 1976’s “Desperados Under the Eaves” by Warren Zevon, which climaxes on that same line about Gower Avenue. Still, it was dislocating, a moment even weirder than when I had read, in February 1998, all the newspaper headlines reading “Carl Wilson dead.”

Most uncanny was that it didn’t seem all that strange. If any musical legend were going to sing your name out of nowhere, him on the verge of 80 and you probably having heard him before you were even born, it would be Bob Dylan. Because a Dylan song can have anything in it, any person, place, thing—any noun, proper or abstract. Including maybe you, at least by coincidence of name. Far more than any elevated guff about poetry or protest or prophecy, that’s the specific way Dylan broke open the popular song, in parallel with the voice he sounded those nouns in, which likewise seemed like it had no business in show business, until it did—because it turned out to be secretly great.

In songs like “Tombstone Blues,” what was afoot was as much standup “sick” comedy as it was Beat and New York School poetry as it was street-corner preaching as it was blues shouting as it was Marcel Duchamp signing a urinal and Andy Warhol screen-printing a soup can: “The ghost of Belle Starr, she hands down her wits/ To Jezebel the nun, she violently knits/ A bald wig for Jack the Ripper, who sits/ At the head of the Chamber of Commerce.” They were amphetamine collages out of Dada and the Russian avant-garde and the Dozens and any kid cutting up magazines and stickytaping bits to the bedroom wall. They made meaning from instinct and impulse and willful accident meeting sound energy. All of which already was alive in the American and global vernacular, of course, but walled off by barriers that his class and race and generational fortune allowed him to vault.

Over the decades, the live wires through which Dylan channeled this plenitude of accumulated signals understandably started to sputter and short more frequently. What came out could get more scrambled or garbled in one song or album, and then crystallize in another. But collage is still the foundation. The concept that Dylan is by nature any kind of storyteller is always misbegotten. Even on a supposedly “confessional” record like Blood on the Tracks, if you try to follow the narratives, they soon contradict and double back on themselves. He usually needs either a borrowed template from another song or a collaborator (like Jacques Levy on Desire or Sam Shepard on “Brownsville Girl”) for any tale to hang together. Hell, just watch what happens when he tries to make a movie.

There are substantial ethical arguments around Dylan’s nonstop plagiarist cabaret, particularly when, like many rockers of his generation, he swipes words or music uncredited and uncompensated from black artists—as detective types have already sniffed out on this album, with the music of “False Prophet” seeming to derive straight from Billy “the Kid” Emerson’s 1954 Sun Records B-side “If Lovin’ Is Believin’.” This kind of thing was sanctioned by the scene Dylan came up in, the 1950s and 1960s folk revival, in which each region and cohort adapting and rewriting the storehouse of collective tunes was simply considered the “folk process.” Thus the tune of “No More Auction Block” became “Blowin’ in the Wind,” among countless other examples. (Though it’s not altogether absent, you’d have to put a gift for melody low on the list of Dylan’s talents.) That’s pretty much been his method ever since, cognizant of the developing conversation around cultural appropriation but outlaw to it, pickpocketing words and cadences from novelists and filmmakers and songs, agnostic to source—including in his own acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2017, a pungent fart in a stuffy church. There’s plenty of room for qualms there, but there’s also a value to having this kind of rascal counterforce to the ever-intensifying regime of intellectual property. Because he’s Bob Dylan, he keeps getting away with (and, granted, making major bank on) the kind of rampant sampling that made the hip-hop era of the Bomb Squad and the Beastie Boys so dizzyingly rich and dense until the courts clamped down.

I’m far from the first to make this sort of case, but I’m recapping it because Rough and Rowdy Ways is the culmination and realization of a new variation on Dylan the collagist that’s specific to his work in the 21st-century as a senior citizen. This is Dylan less as irreverent magpie than as artfully dodging archivist. An archivist of himself, via the documentaries he’s finally cooperated with (though they’re still half-lies) and the extensive official “Bootleg” series (that proved once and for all that Dylan left many of the best songs off his own albums). And an archivist of the world that made him and the world he’s helped make, under the sign of his own mortality or perhaps the apocalypse, which between his cosmic egotism and his (now) elusive religiosity might as well be the same. His hosting of a weekly satellite radio show from 2006 to 2009 seemed to consolidate that curatorial side, its playlists a catalogue of the kind of musical citations that turn up constantly on Rough and Rowdy Ways, a title itself borrowed from a song by early country singer (and blues appropriator) Jimmie Rodgers.

If I didn’t know better, I might almost guess that he’s been chastened by the plagiarism accusations—not to quit stealing but to bring his method right to the surface, building entire verses out of song titles and familiar quotations and classical literary references, with nothing up his sleeve. On this album, the thefts and homages are less a vehicle to self-expression than the very thing being expressed. The mood is elegiac, conservationist, as if the listener is being ushered into Bobby Zimmerman’s Museum of Everything, just off some Minnesota overpass. It’s this feeling of thematic unity that elevates it as Dylan’s best album since at least 2001’s Love and Theft, and with fewer weak spots than any for a long while before that. For once you don’t suspect he’s holding the best stuff back. And yet it also feels as unlabored and stream-of-consciousness as ever.

This sense of Dylan as remix artist is strongest on “Murder Most Foul,” where he beseeches the legendary late sixties and seventies DJ Wolfman Jack to “play” countless songs and singers (along with lines from films and Shakespeare plays and more)—with Jack as an avatar for Dylan’s DJ persona that just happens to share a moniker with President Kennedy and his assassin’s assassin. To Dylan, all these figures are at once objects of his fascination and costumes of the self—as many observers noted when the single came out, his boundary issues around the JFK assassination date back to December 1963, when he ill-advisedly mentioned that he could see some of himself in Lee Harvey Oswald while accepting a civil-liberties award. After a half-apologetic letter, he turned away from writing “political songs.”

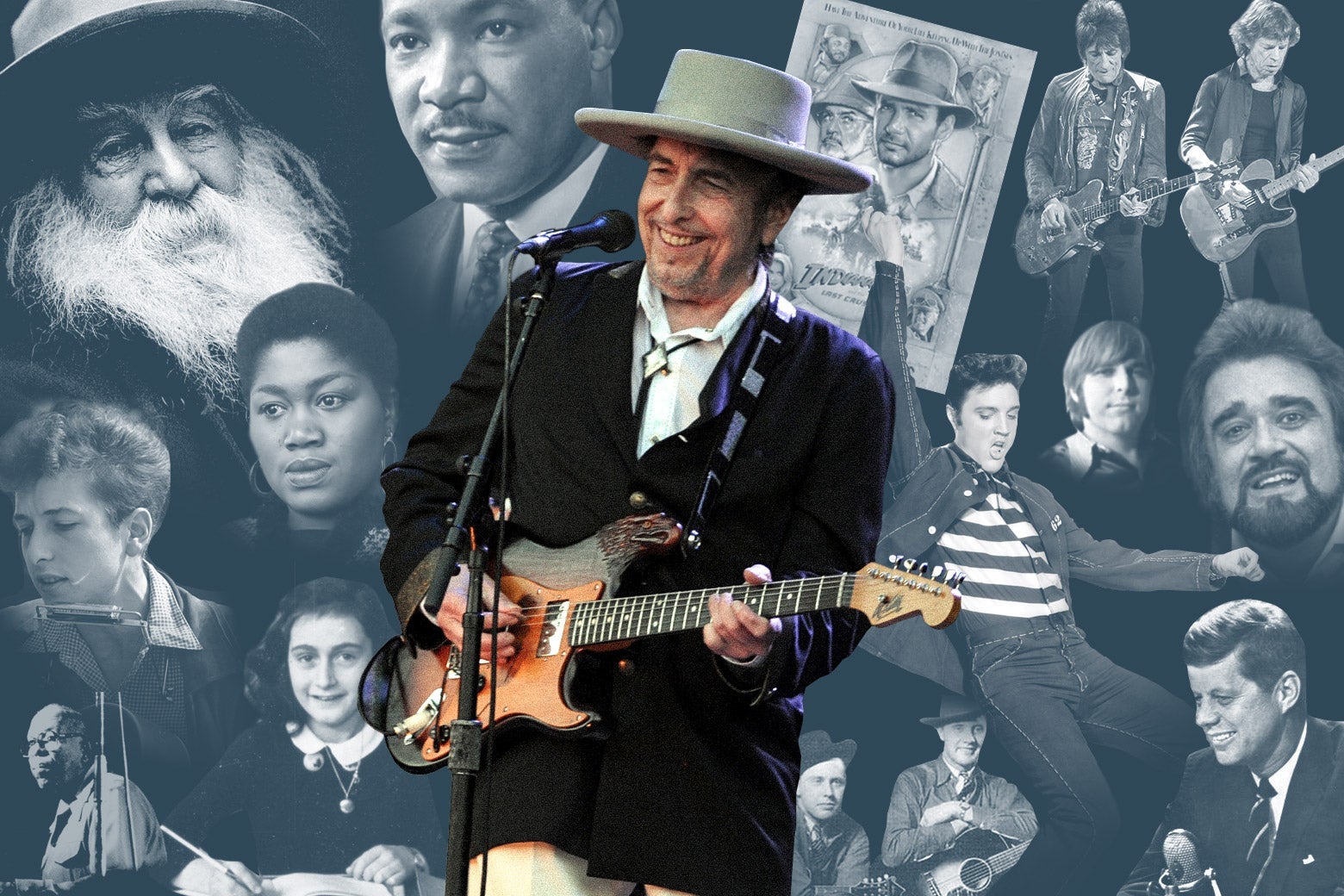

But that’s simply a standout instance of his notorious multiple personalities, for which he’s finally written an explicit manifesto on this album’s opening track, “I Contain Multitudes,” quoting the Walt Whitman line that innumerable fans and music critics have applied to Dylan before. “I’m just like Anne Frank, like Indiana Jones/ And them British bad boys, the Rolling Stones,” he sings, roping a Holocaust martyr, a fictional adventurer, and some boomer rock rivals (with a descriptor straight out of period press cliché) into his maw of negative capability. It’s not only such disparate characters he’s communing with, but entire states of existence: “I sleep with life and death in the same bed.”

Dylan revisits these ideas, with a more outrageous, Bride of Frankenstein-esque twist, on “My Own Version of You.” It begins with the image of Dylan raiding graveyards for body parts to mad-science together perhaps a past lover. But rapidly, as pronouns begin to slip and slide, it starts to sound more like building a self, or a simulacrum of a self, which is to say, a work of art: “I’ll bring someone to life, someone for real/ Someone who feels the way that I feel … I’m gonna make you play the piano like Leon Russell/ Like Liberace, like St. John the Apostle/ I’ll play every number that I can play/ I’ll see you maybe on Judgment Day.”

In the eight years between now and his previous collection of original songs, 2012’s Tempest—a compelling but roiling and growling, uneven batch of doomsday bulletins—Dylan put out three albums of jazz standards, mostly associated with his onetime mutual-antagonist Frank Sinatra, delivered in a version of crooning only Dylan could or would dare. Those records seemed to me partly like an outgrowth of the radio project, but he’s carried forward from them into Rough and Rowdy Ways a vocal restraint and mellowness that otherwise hadn’t been heard from him in a long time. Even on the more hard-blues numbers such as “Black Rider” and “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” (which raises the departed bluesman to the divine pantheon) the raspier, hard-flanged syllables sound like deliberate comic or shock effects rather than (as they could on Tempest) failures of control or, worse, constant death rattles. The drums and percussion, as on the standard albums, are light, and the piano and guitar settings are often quite sparse, giving Dylan’s voice ample room and maintaining the contemplative mood.

That doesn’t mean there’s no piss and vinegar. “Crossing the Rubicon” is a diss-track/battle-rap/crawling-kingsnake number in which, like several times here, Dylan imagines himself as a strutting ancient Roman general, promising, “I’ll make your wife a widow/ You’ll never see old age.” And his philosophical sparring session with Death on “Black Rider,” over an Eastern European folkloric mood, culminates with the singer warning, “Don’t hug me, don’t flatter me, don’t turn on the charm/ I’ll take a sword and hack off your arm.” Although I do have to disappoint some listeners and say that I’m pretty sure the line here many advance reviewers have heard as “the size of your cock will get you nowhere” actually refers to “the size of your cockerel.” But you know, in folk-song-ese, same difference.

But the generally gentle ambience also permits Dylan the space for a song like “Mother of Muses,” expressing his devotion to the creative graces in tones that remind me distinctly of Leonard Cohen in “Sisters of Mercy”—one of several times I wondered if Dylan was thinking of Cohen, perhaps spurred on by the extraordinary albums the Canadian poet (a couple of years his senior) recorded in his late infirmity.

For me, the one song that overstays its welcome is the penultimate “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” It entices with its accordion-led spaghetti-western strains, its first verse half lifted from Bill Monroe’s “White House Blues,” and its tangents about beat-poetry heroes, a quest for a pirate-radio signal, and a shaggy yarn about marrying a prostitute when he was 12. But too much of its nine-minute running time feels like a letter home from a Florida vacation, as if commissioned by the Key West tourism board. As Dylan sings on “I Contain Multitudes,” he paints landscapes and he paints nudes—and I guess I’m crass enough to prefer the nudes.

Many critics and listeners are going to project “timeliness” onto this album, but that’s only because any Dylan album that was released in this particular moment would be apt to contain enough awareness of historic racial injustice (the situation and subject matter on which he cut his teeth during the Civil Rights era) and ample signs of plagues and doom. Instead I think what radiates from Rough and Rowdy Ways is the way in which past and the present intermingle throughout it, as if all the moments of the past century and a half, and back through the Civil War, and back from there through Ancient Rome and the Fall from Eden, were happening at once, and perpetually. A similar sensation is a huge part of the collective intensity and awfulness of the past few months, and years.

The other day I watched Matt Wolf’s 2019 documentary Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, the story of a black communist activist of the 1960s who married into wealth and in the mid-1970s became obsessed with taping all of television news—and much other programming besides—on multiple VCRs, all day every day, for the three decades remaining to her death.* She wanted to document and preserve history as it happened so that there would be a way to disprove the distortions that those in power would bring to the stories when they told and retold it later. On one side, she was a hoarder, whose home and storage spaces filled up not only with the tapes she was recording but all kinds of other stuff as well, seemingly out of an inability to let anything go. But the documentary questions what kind of credentials make us declare someone a hoarder instead of a collector or a curator. Stokes was also a prototype of the kind of “information activist” that is more familiar to us now in internet culture. (And the internet is where her archive is destined now.)

In many ways Dylan is that same kind of force and living archive, his mind and his songs loaded with decade upon decade of 24-hour news and fiction and fable and conspiracy, and he is left alone to tell the tale, at least as he understands it, in his own meld of mangled mythology, solipsism, and bearing witness. No one can guess how much more he’ll have to relate in his ninth decade, but if Rough and Rowdy Ways turns out to be the last bequest and testimony of Bob Dylan, it’s a vault almost capacious enough to hold the whole—if you listen close, perhaps even his own, pilfered version of you.

Correction, June 19: This article original misidentified the director of Recorder as Matt Ward.