Editor's Note: This story was reported shortly before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. The tours it mentions have been postponed, and the businesses that comprise Rock Lititz face an uncertain future. Please keep their present circumstances in mind as you read.

In 2019, BTS became the first band since the Beatles to release three number-one records on the Billboard charts in the same year. One song amassed 74.6 million plays on YouTube in just twenty-four hours. They sold out Wembley Stadium in ninety minutes, were named one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People, and set the Guinness World Record for the most Twitter engagements.

BTS is an international juggernaut. And all that is making Gary Ferenchak a little nervous.

Ferenchak, who’s fifty-six, sleeps some nights in a double slide-out CrossRoads Zinger camper in the gravel lot at the edge of a cornfield in Lititz, Pennsylvania. Parked outside is a ’95 Subaru Legacy, his regular drive, and a ’92 Geo Tracker with locking hubs, which he’s trying to sell. Next door is a building known as the Studio, a fifty-two-thousand-square-foot box sheathed in matte black sheet metal. It stands one hundred feet tall and has four loading docks and a door that a semi can drive through. A grid of steel beams along its ceiling can hold up to one million pounds of chains, motors, bumpers, trusses, lights, speakers, and screens. The Studio is the greatest rehearsal space in the world, used by the biggest acts in the world. Including, in a few weeks, BTS. They have booked the Studio for almost a month to practice for their summer tour.

The Studio is part of a larger operation called Rock Lititz, a ninety-six–acre campus that also sports a hotel and a cluster of businesses specializing in live-event production—concerts, as well as product launches, theme parks, cruise lines, and e-sports.

Anything live and huge.

The town, in Lancaster County, has been home to a sound company and a staging company for decades. But since opening the Studio in 2014 and establishing Rock Lititz, its owners have adapted to the new reality in the music industry: Record sales are a fraction of what they once were, and while streaming has helped the bottom line, the big money is in touring. For a major band planning a major tour, the companies that constitute Rock Lititz aim to be a one-stop shop: They build the stage, they design the lighting, they do the sound, and after a couple days or a week or a month of rehearsals, they send you off to tour the world.

BTS is sending ahead thirty shipping containers of equipment, which will become Ferenchak’s temporary new neighbors. The production will be one of the biggest that Rock Lititz has hosted—as massive as Taylor Swift’s Reputation tour in 2018, which became the top-grossing concert tour in U. S. history.

The first time he saw the Studio, Ferenchak thought, This looks like an organ-harvesting facility. Ominous. A big black box in the middle of nothing.

That was back in 2014, when he retired from life on the road, after twenty-five years as a sound engineer, to join Rock Lititz as the Studio’s production and operations manager. He takes care of anything within its walls: ensuring the day’s local labor is set, checking in on catering, answering a truck driver’s question at the dock, replacing toilet paper. Once, during rehearsals for her 2016 Formation tour, Beyoncé needed someone to administer her B12 shot. It was Sunday night, and Ferenchak thought at first he’d have to call in the only ambulance service in Lititz. Then he realized he didn’t: His niece, a nursing student who was moonlighting as a show runner, was qualified to administer it.

Sturdy, built like a barrel, with a thick gray beard and slate-blue eyes, Ferenchak is always in shorts, cargo pockets preferred. The camper is only for late nights. He owns a house fifty miles east, in Pottstown, a bungalow with a three-car garage out back. Outside, under covers, sit two Mustangs and a Triumph. Inside the garage are another Mustang, six motorcycles, an ’87 Mercury Colony Park wagon, and eighteen bicycles.

The commute is not ideal, and a camper isn’t a home. But he makes it work. Besides, Ferenchak likes this weird oasis, Rock Lititz, where a band of smart and resourceful misfits build dreams for superstars. A few years ago, David Byrne came to practice for his show American Utopia, and it fell to Ferenchak to pick him up at the Lancaster train station. As they wound past centuries-old farms, Byrne was mostly quiet, scanning the landscape. He waved at an Amish woman on a scooter bike, bonneted and barefoot. She waved back.

Ferenchak takes great pride in the Studio. But more than that, he is proud of the community that built it, the people he works for and with. He looks forward to the moment an artist first walks into the space, marveling at the grid, high-fiving over the eight gray electrical boxes that provide up to thirty-two hundred amps of electrical current. But it is the size of the room, its vastness, that causes jaws to slacken, eyes to gaze upward, silent awe to settle in.

Ferenchak has always been better at taking care of others, which he chalks up to his days on the road, being the guy behind the guy. To him, self-care is a pair of comfortable shoes. He could move closer to Lititz. First, he’d have to clean out the garage in Pottstown, and . . . bahhh.

But most of his friends live in Philadelphia, and getting together is harder each year. Might be nice to live and work in the same place. Have a life.

Maybe he’ll look into it once this BTS thing is over.

How does this happen? When a place becomes so closely associated with an industry or a thing—the Louisville Slugger, Carolina barbecue sauce, Silicon Valley tech—we assume there were faceless market forces at play. How did Hartford come to be the insurance capital of the world? Who knows? But there’s always a story, and that story is never about market forces.

It’s about people. Why is Lititz, Pennsylvania, population ninety-four hundred on a good day, a mere two-point-three square miles, suddenly the place where every touring megastar must go?

There is indeed a story, and it is a story about people.

There is a truism in the tech world: As time passes, hardware shrinks. Speaker columns that decades ago weighed six thousand pounds each? These days they’re twenty-five hundred. The cargo space required to fit audio gear has gone from two trucks to one, then to three quarters, then to two thirds.

Which, far from saving tours money, just means there’s room to add more stuff to the show. Whereas artists once needed only a lighting technician and a sound technician, they now have a video person, an automation person, maybe a laser expert, maybe even a drone operator. Touring plays a much larger role in a major artist’s revenue stream—around 80 percent—than it did in the days when fans paid for albums. In 1999, the year Napster launched, music sales in the U. S. totaled $22.3 billion. By 2019, that number had dropped to $11.1 billion. At the same time, ticket prices nearly quadrupled, from $25.81 in 1996 to $96.71 last year, and so did the spectacle of each show. Fans are not just paying to make up for lost album sales; they’re paying for the drone operator.

Every show has to be perfect. Artists and their crews need to practice. Before Rock Lititz, the venues available for rehearsals typically included the local crumbling hockey arena. The production office? A locker room that might as well have been inside a jockstrap. This grew increasingly annoying as shows became more ambitious, requiring more rehearsal—and more time in the jockstrap.

With the Studio, artists now have a place for all that. Once Hotel Rock Lititz opened in 2018 and their bed was across the parking lot? That was just icing.

Business is good, in part because of the Studio’s fair rates: $7,500 a day, give or take, mostly inclusive. For tour managers who budget $10,000 a night on hotel rooms alone, that number doesn’t raise one hair of an eyebrow. In its first year, the Studio was at about 30 percent capacity; last year, it was booked at around 85 percent.

The story of Rock Lititz starts with a Christmas gift.

In 1955, a man named Roy Clair, who used to work in the local mousetrap factory before opening a grocery store (Clair’s), bought a PA system for his two sons, Roy Jr., twelve, and Gene, fifteen. The Lititz boys had taken an interest in helping out with the sound for sports events and school dances.

The middle class was rising after World War II, and teens started carrying more pocket change, a lot of which they spent on LPs and 45’s. Record labels spotted a new revenue stream: Send their rosters out on the road. Musicians were getting used to the technological advancements in recording studios and were losing patience with playing their hits through tinny speakers strung up at the local rec center. But there was no such thing as an audio company dedicated to touring.

The Clair boys kept working local gigs. In 1966, they were asked to run the sound at a Dionne Warwick show at nearby Franklin & Marshall College. That led to a job with Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, and Valli invited Roy and Gene to work again on a three-night run in Columbus, Toledo, and Cincinnati. The brothers netted forty dollars. As far as anyone could tell, it was the first time an audio company had gone on tour.

Lititz began as a planned community, built in 1756 by the Moravian Church, in the middle of Warwick township, which surrounds it like a doughnut. For the next century, only Moravians, an old Protestant denomination, were permitted to live there. Opened to non-Moravians in 1855, the town fostered a culture of diligence and rectitude that was passed down to each generation.

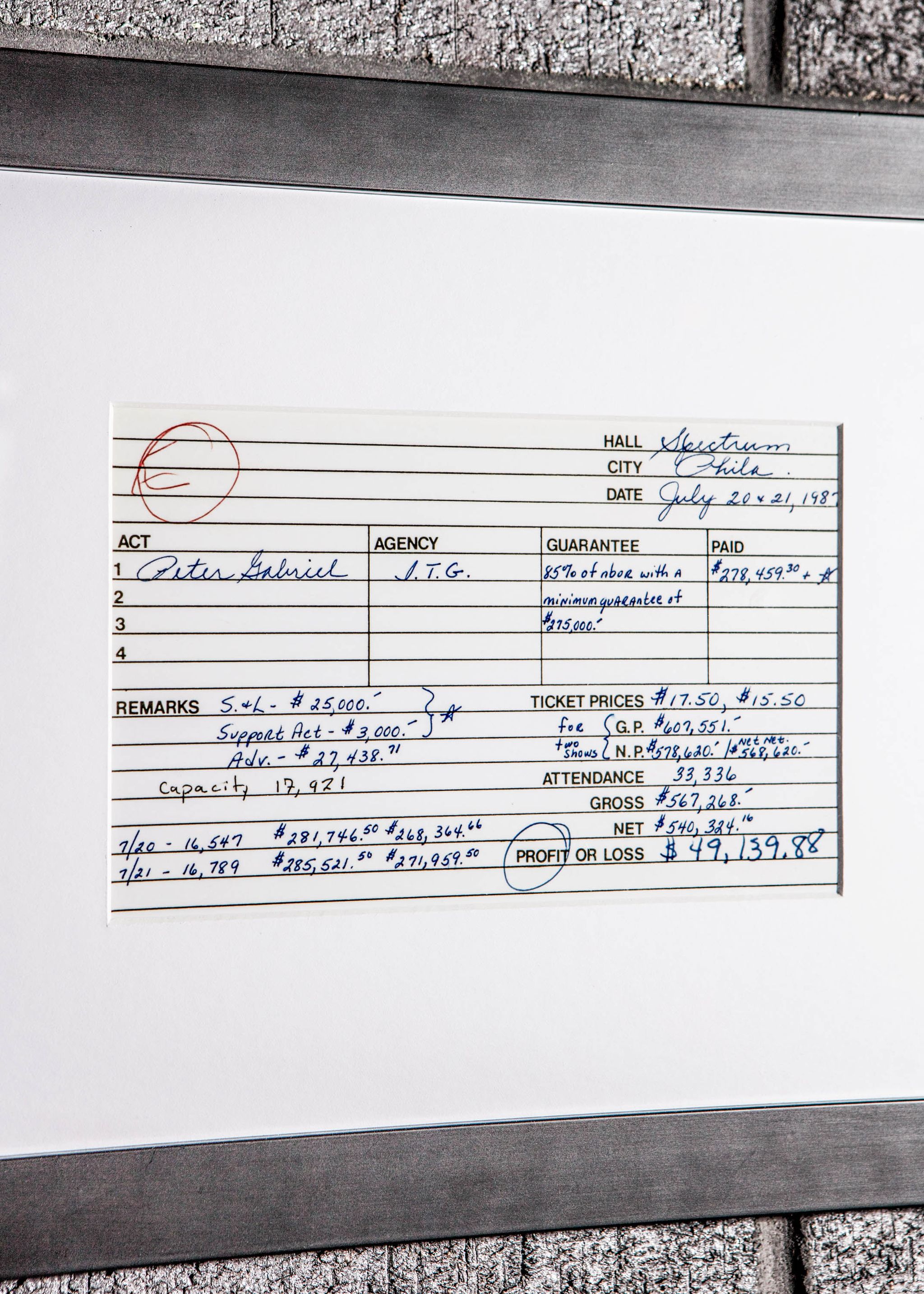

Roy and Gene were very much of the place they were raised: hard workers, not hippies, looking for opportunity, not easy money. When Frankie Valli advised them to leave Lititz if they wanted to make it big, they left Frankie Valli. The Four Seasons had gone stale anyway, and the brothers felt they needed to impress a band with more clout. In 1968, they did, at the Spectrum in Philadelphia. The headliner: Cream, for their farewell tour.

This article appears in the April/May issue of Esquire

Subscribe to Esquire Magazine

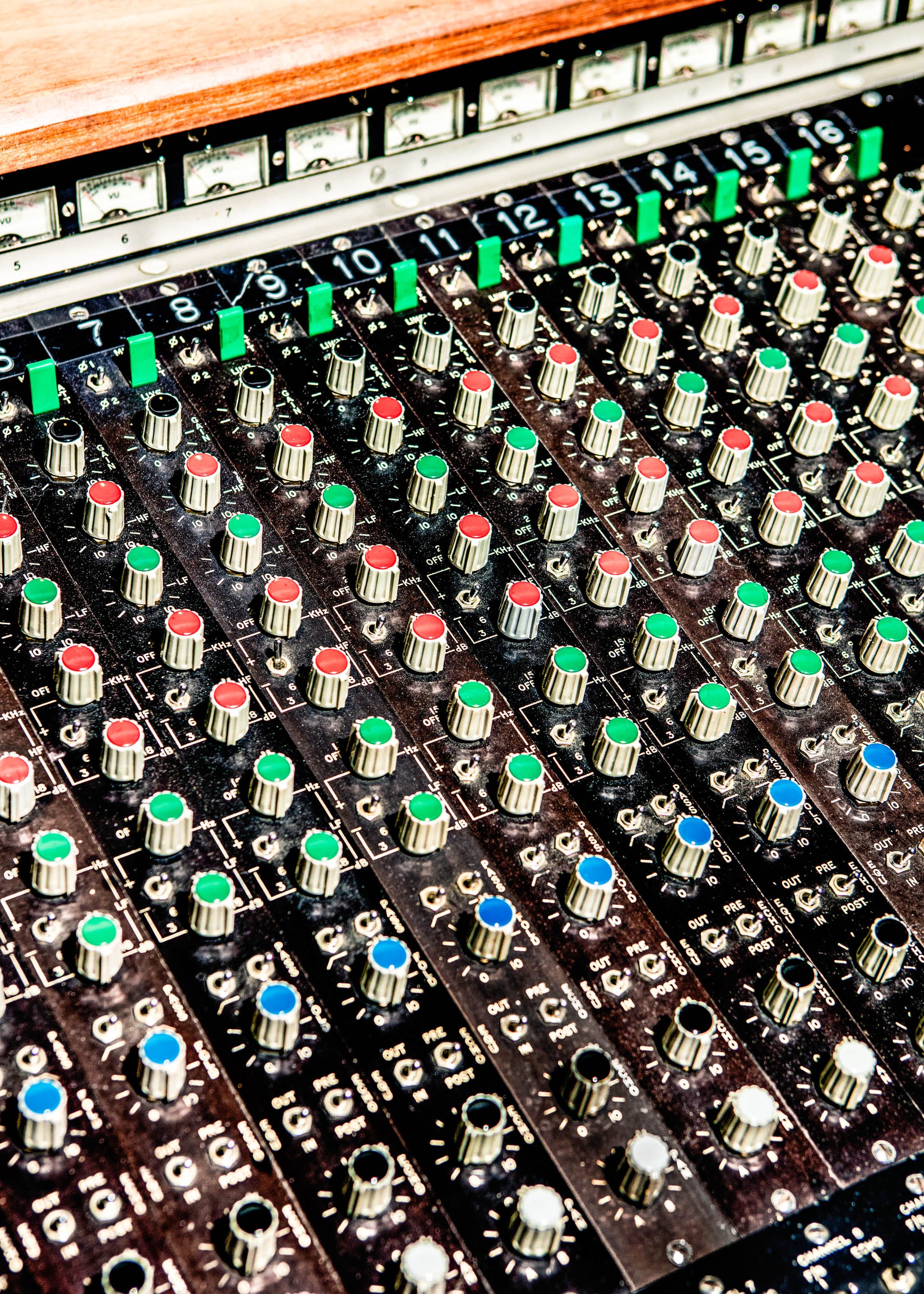

The Clairs had never worked an arena, but they knew that the tube amps of the time stood no chance of filling the space with sound. They found what they were looking for in the Crown DC 300, the first widely available solid-state amp, by Clarence Moore, an Indiana minister turned engineer.

Cream onstage, with the Clair brothers at the soundboard? They shook the rafters.

Russell Snavely entered the story in 1974, when he took a job at what was now Clair Brothers Audio.

Snavely is sixty-seven now, as lean as he was growing up in Lititz. Lived here his whole life. He graduated from Warwick High, just like his parents, and got a job at a planing mill, putting to use the woodworking skills he’d learned from his grandfather, a builder of lawn ornaments. One night, at one of his haunts, Snavely struck up a conversation with some guys from Clair Brothers who needed help loading gear for an upcoming tour with the prog-rock band Yes. Snavely jumped. Why? “Three words,” he says. “Sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll.”

But he was good with wood, so instead of having him go on tour, Roy and Gene put him in the shop—which, beyond the obvious bummers, earned him thirty dollars less each week than road pay.

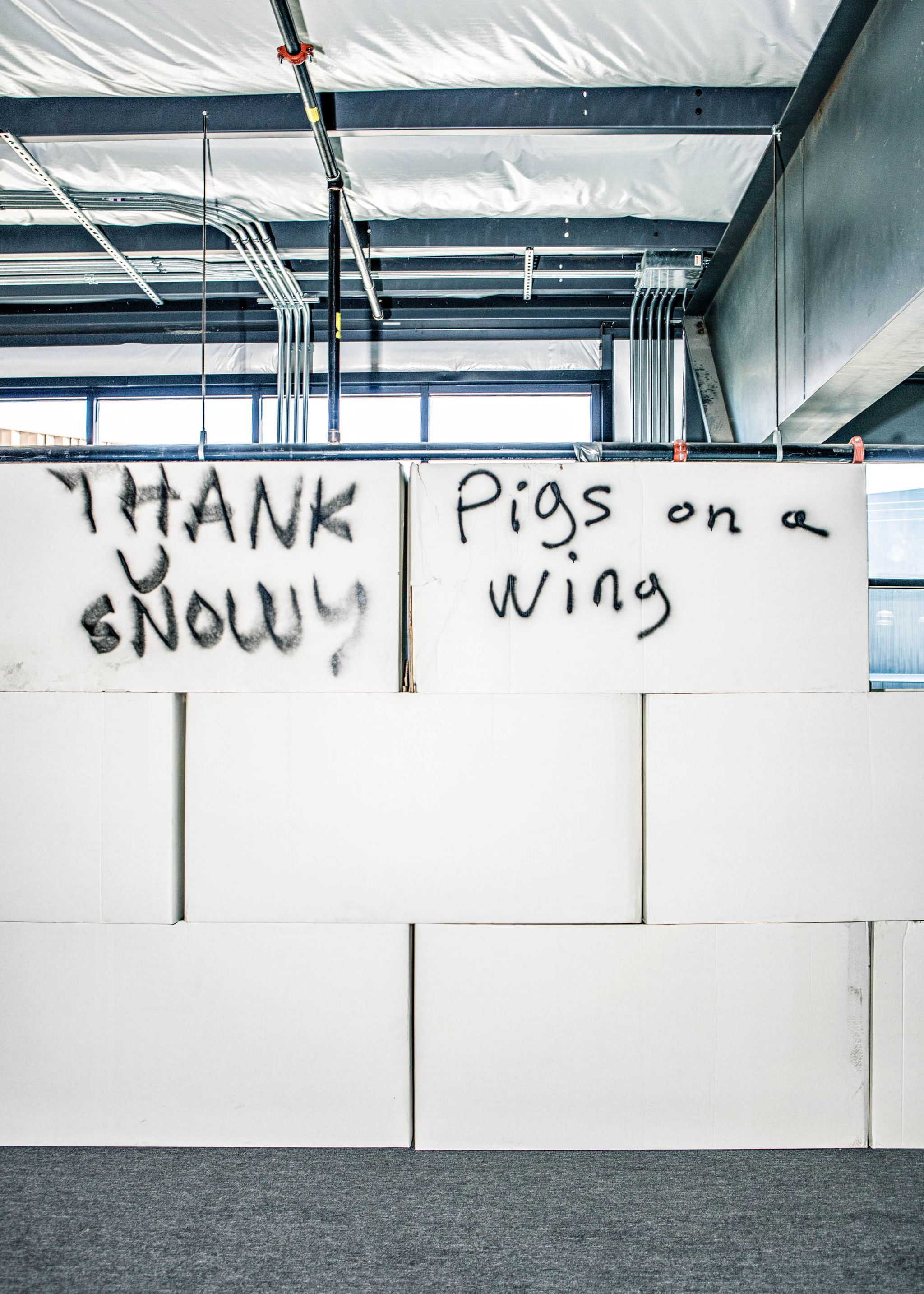

One of Snavely’s first projects was building the S4, a four-way speaker in a box of birch plywood, with a mix of woofers, midranges, and tweeters that together covered the full auditory spectrum. Each cabinet weighed about 425 pounds. By attaching sixteen S4’s on a bumper bar and raising them above the crowd, Clair Brothers introduced an entirely new way of rigging audio: Rather than sending sound waves along the floor level, as ground-stacked speakers did, the flown speakers blanketed the crowd from on high. The acoustics improved for every seat in the house, even the nosebleeds. Mick Jagger first heard a cluster of S4’s in Los Angeles, at one of Rod Stewart’s last shows with Faces, and decided the Rolling Stones must have the speakers, too.

The S4 marked the moment that Clair Brothers Audio went from a sound company to a sound-reinforcement company—capable of building and breaking down massive audio systems in mere hours. The S4’s were designed for portability: They fit two wide in the bed of a semitruck, with no wasted space. Turned 90 degrees, they fit four wide in a European truck. Costs went down, and so did load-in times. And the space the speakers saved—it was as if Clair Brothers had expanded the capacity of every truck on two continents.

His second week on the job, Snavely worked eighty-two hours, which he’d never done before and hasn’t stopped doing since. The same passion he and his coworkers put into the job, they put into partying. One time, he joined a caravan of trailer-hitched station wagons heading to Tampa to run sound for Ike and Tina Turner. By the time they hit the Maryland state line, Snavely’s car had polished off a six-pack and a couple of joints. The border is barely thirty miles from Lititz.

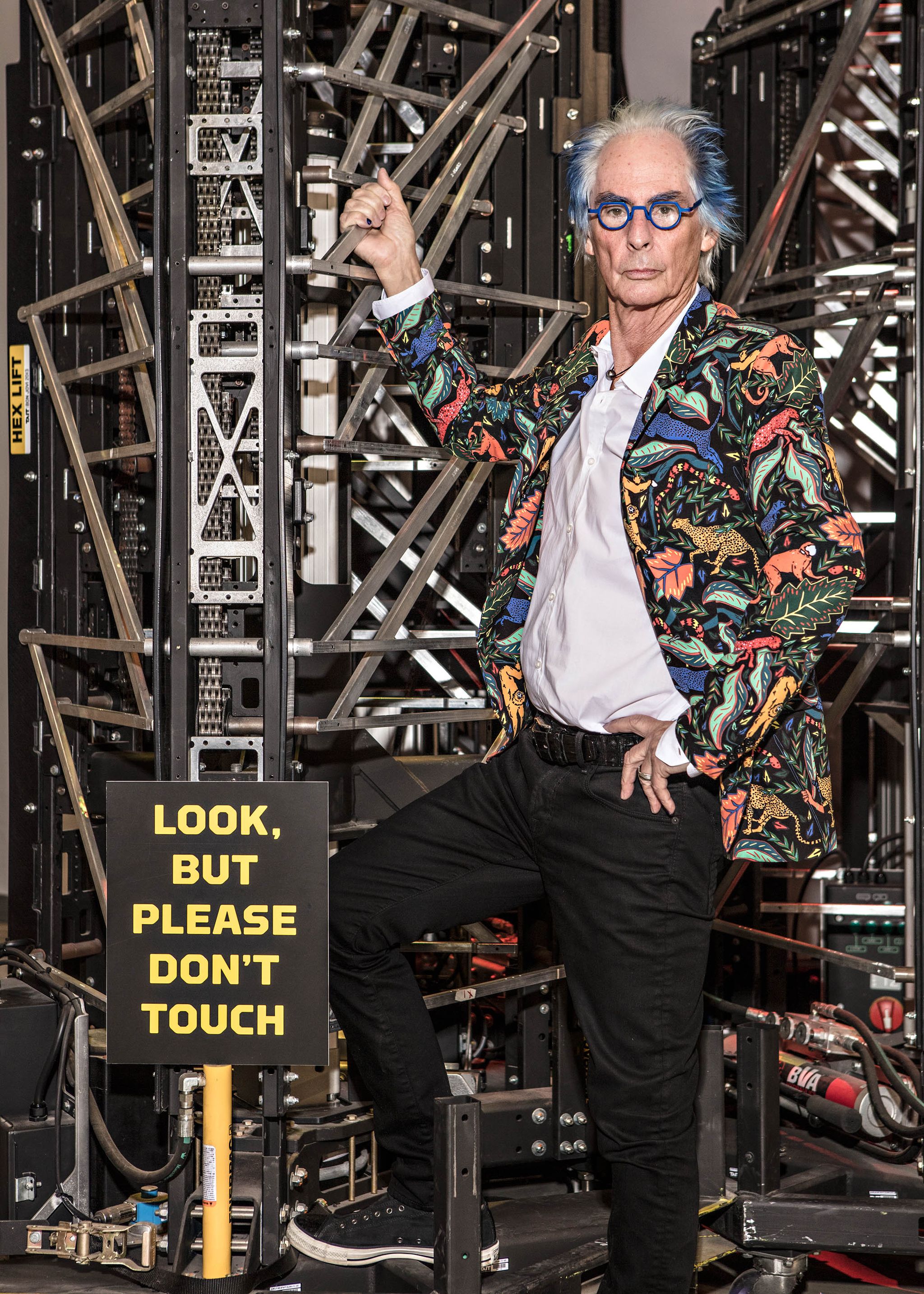

While on the road with Yes in 1974, the Clairs met Michael Tait, a wiry, wayward Australian who was managing the band. Tait had taken it upon himself to run their lighting. He didn’t buy gear; he made it. He constructed his first rig out of twelve-volt fog lights in coffee cans, steel pipes, and resistors sourced from a military-surplus shop.

The Clairs liked him instantly. Tait knew how to read people. “I found I could understand the psychology—of the audience but especially of the musicians,” he says. Once, he received a sketch for an Elton John stage that would have placed the drum kit on a riser at the level of John’s ear. “It would’ve driven him nuts,” Tait says. “You must make everything so it works for the band. When the band is grooving, the audience is grooving.”

Eventually, the Clairs convinced Tait to move from London to Lititz. Here, in 1978, he devised plans for rock’s first rotating stage, which he pitched to Yes as a win-win: The audience would have an intimate experience, and the band could sell more seats.

Problem was, Tait had no space to build his creation, so he turned the Lititz Elementary gymnasium into his makeshift workshop. Roy and Gene were also renting space in local schools; artists had started coming to Lititz to test the equipment before heading out on tour. But they could only do so when school wasn’t in session. Even then, problems could arise. When Peter Frampton practiced at Manheim Township High, hundreds of teens showed up.

No more of that. Together, Michael, Roy, and Gene purchased an old box factory on a back street in Lititz. They gutted its largest wing, installed a four-ton I beam near the ceiling, and repurposed its hickory flooring into walls for the control room, which they filled with $150,000 worth of equipment. A rehearsal space, four thousand square feet and thirty-five feet tall.

A proto Rock Lititz.

They finished just in time for the arrival of its first client, Billy Joel.

In another wing of the factory, Tait built a workshop for his new lighting company, named after a light tower he’d built that collapsed into its crate and expanded back out of it via a telescopic gas cylinder: Tait Towers.

But automated lighting was a growing business, spearheaded by companies with R&D budgets larger than what Tait Towers could hope to make in a year. Meanwhile, word had spread about Yes’s rotating stage, and orders were rolling in. Tait followed the money, pivoting toward stage construction.

It wasn’t always smooth. In 1982, while fabricating a stage for Olivia Newton-John, one of his woodworkers nearly gave himself a vasectomy with a table saw.

Snavely, too, was having problems. He had taken the drugs part of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll a bit too seriously and had been given an ultimatum by Roy Clair: Get clean or get out. He’d gotten out. But he needed work, and Tait hired him to fill in for the injured employee.

Over the years, Snavely helped make a rotating stage for Barry Manilow that was pushed manually by concealed stagehands. He went on tour with a star-shaped stage for Kenny Rogers, and he did a lot for Metallica and AC/DC.

As more money came in, the industry moved away from the party life, became more professional. When Snavely began at Clair Brothers, you had to pass the roadie test to go on tour—lifting a hundred-pound speaker horn above your head, proving you know your ohms from your amperes. All of a sudden, you needed a certification to set foot on an arena floor. More new hires had college degrees. Roadie became a bad word. Snavely felt squeezed.

But he got clean. In 1998, with Michael Tait’s support, he checked into a facility. “I was the first one at Tait to do a lot of things,” Snavely says. “Rehab’s one.”

He hasn’t had a drink in twenty-one years.

This was supposed to be it—the big night.

Ned Pelger stepped out of the Studio and walked across the cornfield to the top of a small ridge. Inside, Usher was onstage, ringed by dancers, rehearsing for his 2014 UR Experience tour. His sweet voice spilling out of dozens of Clair speakers. Inside, it sounded like an arena concert.

Outside, Pelger didn’t so much hear the music as feel it—a deep, pulsing ripple that jiggled his guts. He began to feel nauseous. Pelger was the building’s engineer of record and had overseen its construction. They’d completed the job not a month before. And now “Love in This Club” had transmuted the Studio into a massive subwoofer. We’re in trouble, he thought.

Pelger was more than just the contractor; he was family. His cousin Skip was married to Roy Clair. While still at Warwick High, Pelger went on tour as a roadie with Yes. In 1978, Pelger took a year off from college to work as a roadie for Bruce Springsteen’s seven-month Darkness on the Edge of Town tour. Springsteen demanded perfection. During sound check at each new venue, while the E Street Band ran through song after song onstage, he walked the seats, listening for dissonance. Joining him were Clair Brothers’ top lieutenant Bruce Jackson and cousin Ned. Anything Springsteen didn’t like, he asked Jackson to fix, and Pelger took notes. They called him Nedly. “Go tilt that speaker, Nedly!” “Hang more drapes to stage right, Nedly!”

He knew he couldn’t keep touring and stay married to his high school sweetheart, Debby, so he settled in Lititz and went into construction. For a long stretch, his path did not overlap much with rock ’n’ roll’s. In the mid-nineties, he left his position at the top of a local construction company and launched his own business. His first major project was Clair Brothers’ new headquarters, in Warwick, just north of Lititz. Its address, 1 Ellen Avenue, was named after Roy and Gene’s mother.

Around 2011, the township manager approached Clair Brothers and Tait Towers with an offer: A ninety-six-acre farm abutting Ellen Avenue was available. If the town rezoned the land from agricultural to industrial, would they be interested in buying it?

By that time, the bond between the two companies had weakened. Both were under the second generation of leadership, and both were undergoing change. Troy Clair, Gene’s son, had overseen an international expansion of the business, which was now called Clair Global. Under Adam Davis and James “Winky” Fairorth, two of Michael Tait’s protégés, Tait Towers started looking for opportunities outside of rock ’n’ roll.

Land was what they both needed. But neither needed that much.

Troy Clair, Davis, Tait, and Fairorth split the down payment under a new LLC named Rock Lititz and only then began thinking about what they’d do with the land. Someone floated the idea of a rehearsal space. If nothing else, it would make a great marketing tool.

In March 2014, they broke ground on the Studio. Pelger pushed his crew hard, and construction was done in just six months. He’d priced out how much it would cost to soundproof the building, and everyone agreed that it was too expensive. After all, it was in the middle of nowhere.

Now Pelger stood on the hill, and his guts were jiggling.

The sheriff pulled up, having received more than fifty noise complaints, and shut the place down. Usher and his crew were shuttled to a field house at Temple University, in Philadelphia.

U2 was scheduled to arrive at Rock Lititz in six weeks, and the Studio was unusable.

The town called in a noise-abatement consultant. Rock Lititz called in three. The Studio’s walls, made of a light-gauge metal with fiberglass insulation, absorbed the high-frequency sounds but not the low. As Usher performed, bass waves had carpeted the surrounding land in every direction. The only way to dampen them in the future was to add mass.

Various solutions were discussed: building another building over the one already there, at the cost of $10 million. Lead: phenomenal sound blocker, but way too pricey and potentially unsafe. Water was excellent, too—could a waterbed stick to a wall? Sandbags sounded . . . gritty.

Then Pelger, having hit pause on a book manuscript he’d begun to write—Great Sex, Christian Style—thought, What about shotcrete? The sprayable concrete used to make swimming pools—it was as cheap as crushed stone.

Pelger called a fellow congregant of his church, Lives Changed by Christ, who was ex-Amish and a current shotcrete specialist. The man came down to the Studio, placed rebar against the wall, and started spraying. The shotcrete held. Over the next ten days, four million pounds of it were sprayed on the walls inside the Studio.

E.H. Beiler Industrial Services specializes in pre-engineered metal buildings. Its founder, Ezra Beiler, is a member of the Plain community, as the Amish call themselves, one of a family of thirteen. He attended a one-room schoolhouse through ninth grade, then was expected to start working. He knew he didn’t want to follow in the footsteps of his father, a farmer. Beiler had farmed every day until he was fifteen, despite a bad eye and a limp when the weather is bad, the remnants of a polio infection he contracted as a boy. The routine had bored him. “It’s everything over and over again, know what I mean?” he says. “You milk the cow; you milk it again.”

Ned Pelger brought Beiler in to erect the Studio and has brought him back for each phase of Rock Lititz’s expansion. When Beiler passes by the campus—Plain people can’t drive, but they can be driven—he doesn’t think of how out of place it looks or of the increased traffic. He doesn’t think of the three-thousand-odd steel sheets it took to drape the Studio. He thinks, There’s another one that created good jobs.

It’s early spring, and work for Beiler and his twenty-four employees will soon pick up, including the next round of expansion at Rock Lititz. The first three buildings went up over five years; they’re constructing the next five in just eighteen months. Pelger just sent over the contracts. The new Studio and Pod 1A: $4.6 million. Pod 5: $2.3 million. The new Clair Global headquarters will be somewhere in between.

Beiler estimates that when he was a kid, 10 percent of the Plain community worked in construction; today, it’s more like 70 percent. In the 1960s, government officials refused to allow Plain Sect milk to be sold unless it was refrigerated, and the community leaders weren’t about to put their people out of business, so they allowed milk to be cooled. Today, there are even Amish electricians. “As time goes on,” Beiler says, “technology changes things.”

Church leaders provide guidance, but you have to let your conscience be your guide. Beiler wouldn’t build a beer distributor, but he decided Rock Lititz wasn’t a problem.

After the Usher incident, Andrea Shirk, the general manager of Rock Lititz, received a call from a rep at Live Nation. “He’s like, ‘Are you seriously moving Usher?’ I was like, ‘Yeah.’ He goes, ‘Just so you know, we get noise complaints all over the world, and we tell them to fuck off,’ ” she says, with a throaty laugh. “I said, ‘That’s lovely. But that’s just not how we operate here.’ ”

The Studio closed on Sunday, and a township meeting was held on Wednesday at the Warwick municipal building. “Troy was in Florida. Adam was like, ‘Uhhh, I’m not available that day,’ ” she says. Shirk went alone.

One resident after another stood and voiced complaints. Margaret Ketchersid said she’d been excited about Rock Lititz because of the jobs it would bring, but now she worried about the structural integrity of her house—and its property value. Earl Diffenderfer said he and his wife had moved to a fifty-five-and-older development because it would be quiet, but now their house rumbled. What would it be like once the leaves fell off the trees? Marilyn Taylor said she’d felt vibrations all through her house, that they’d made her feel sick.

“It was a mob in there,” Shirk says. In the weeks that followed, she and Troy Clair went door to door to conduct pre- and post-shotcrete testing, and to ensure their neighbors felt okay at every step.

Without Shirk, Rock Lititz wouldn’t exist. She figured no lender would back a world-class facility with zero clients, in a cornfield. If the concept failed, what was a bank going to do with a one-hundred-foot-tall one-story building? The only way forward was with government support, so Shirk got a $3 million grant from the state. She secured the resources to restore the floodplain on the Santo Domingo Creek, which had been buried by tilled soil over the decades. The creek now flows across the property as it once did, and Rock Lititz gained a couple more acres to build on. Before the shotcrete on the Studio walls had dried, Shirk moved on to the next phase: a $22 million, 252,000-square-foot building intended to house live-event production companies.

Looked at one way, Pod 2, as it’s known, is a commercial office space. Shirk is the landlord; the twenty-seven businesses are her tenants. But there’s more to it. It’s a collective of creative, hardworking, like-minded people. An ecosystem with cross- pollination. With synergies.

That’s the hope, anyway.

And that’s what motivated Shirk to take the job. When she left Bose, outside Boston, and moved to Lancaster—her husband is a twelfth-generation Lancastrian—she walked away from leading a hundred-person team. Rock Lititz offered the chance to do more than crank out a product.

It was mostly up to Shirk to decide which companies got space in Pod 2, and she selected based on who she thought would “enhance the Rock Lititz brand.” Leases are for ten years, so she thought long and hard about the right mix. Its largest tenant is the production company Atomic, which has been in Lititz since the early nineties, when its founder, Tom McPhillips, the set designer for the MTV Unplugged series, moved to be close to Tait and Clair. Others include specialists in pyrotechnics, barricades, and shipping logistics. When a new tenant arrives, Andrea sends them a welcome box of cookies.

Two hundred seventy-five people work in Pod 2. The building has common spaces, a smaller rehearsal space, a café, and a brewery. A gym with a rock-climbing wall? Check. A health clinic? That’s equipped to provide vaccinations for those who need them before touring overseas? Check and check. You could spend months there without needing to leave. Or you could walk across the parking lot and book a room at Hotel Rock Lititz.

Shirk oversaw that project, too.

Building buildings isn’t an issue. The bigger challenge is building a community. Most of Shirk’s staffers are women, but it’s a small team. Men dominate the companies of Rock Lititz, as they do across the industry. And diversity? That’s a problem in the industry and in the area. The city of Lancaster has one of the fastest-growing Hispanic communities in the state; four in ten of its residents are Latino. But the rest of the county is among the whitest you’ll find in America. In Lititz, just ten miles north, 96 percent of inhabitants are white.

There are other struggles. People have tried to copy the Rock Lititz business model—one in Delaware, another in Las Vegas, a few in Nashville. Anyone with time and money can build a replica, but you can’t just up and construct a dynamic collaborative environment. To make Rock Lititz uncopyable, Shirk believes it must invest in the next generation. One of the tenants she selected for the next round of expansion—which will cost around $42 million in total—is a music school, and she recently spoke to hundreds of area middle school girls about how cool it is to study and work in a STEM-related field.

She’s trying.

Shirk can do all this because she has the backing of the Rock Lititz owners. When Troy Clair first asked her to run the business, he said, “Boy, we can’t get shit done. I just need an adult in the room.” That’s how he introduces her: the adult in the room.

How do you define a community? Measure its contours? Rock Lititz is a community. Amish country is a community. Rock ’n’ roll is a community.

Adam Davis, Tait’s chief creative officer, likes to say there are two kinds. One is Lititz and the surrounding towns. It’s the community to which the Clair family is most devoted. They’ve remodeled churches and rebuilt the rec center. Roy served as the mayor of Lititz for eight years. They maintain a public baseball field on the front lawn at 1 Ellen Avenue.

The other kind of community is the international network of the live-event industry. “There’s this ecosystem that exists in the back halls of every amphitheater and arena in the world,” he says. “When you drop into it, you’re amongst your peers, and when you leave, you’d never know it exists.”

When Michael Tait retired in 2006 and Davis and Winky Fairorth took over, Tait Towers was a rock ’n’ roll company. Today, concert touring makes up a third of the business. Tait has fourteen offices around the world. Last year, half of the twenty highest-grossing North American tours were by musicians fifty-five or older. “We thought a lot of our clients were going to die and we’d be out of business,” says Davis. “So we thought we’d better diversify.”

The next generation at Clair Global is grappling with the same concerns as Davis. “I mean, live entertainment is great,” says Shaun Clair, who, with his brother Matt, will likely take over the business from their father, Troy. “But is it exponential? No.”

Rock ’n’ roll, on its own, is no longer enough.

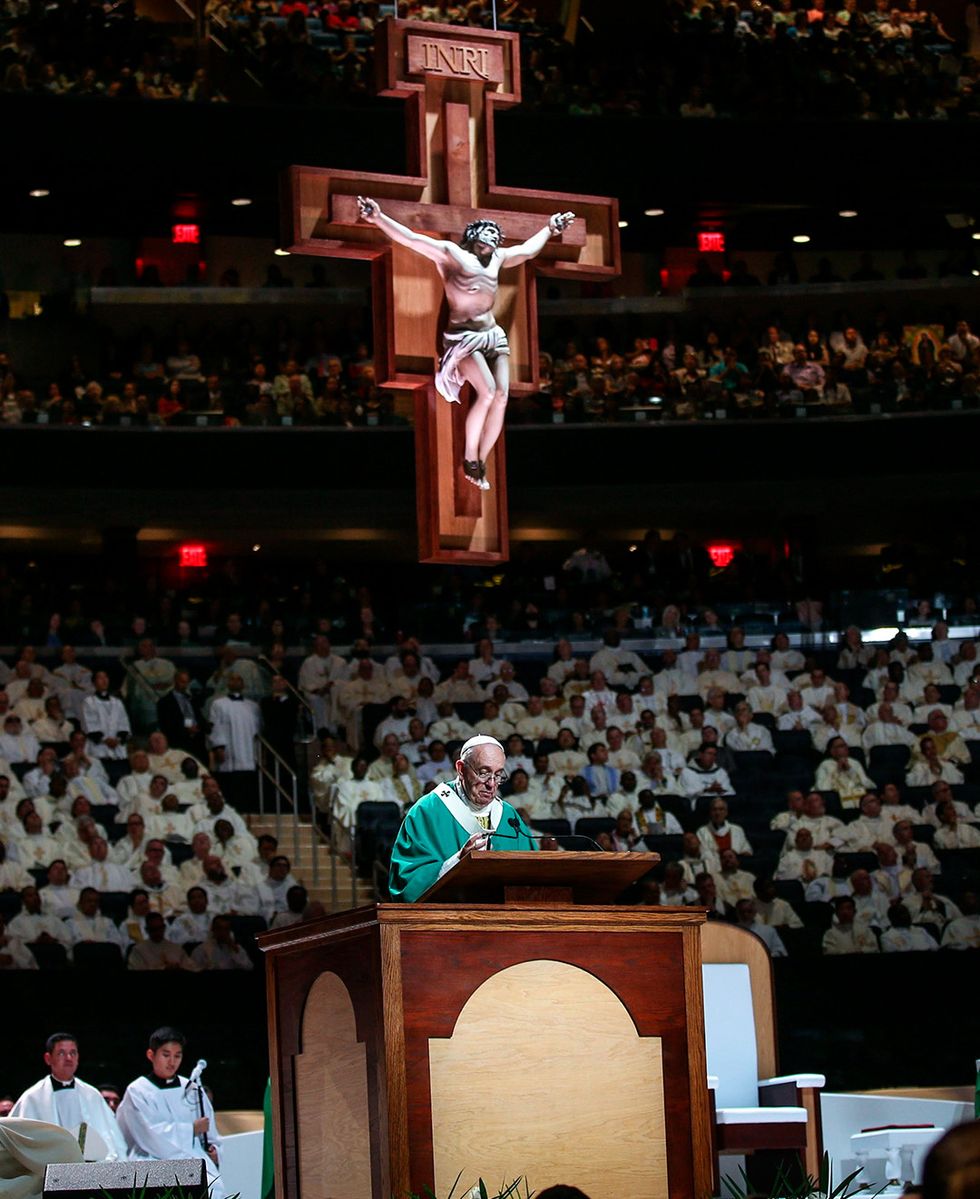

Clair has been growing its installation business—sound systems for megachurches and stadiums. They’re focusing on “rapidly deployable networks”—temporary WiFi for big events. They wired Madison Square Garden for Pope Francis in 2015 and ran the audio. Tait carved the twelve-foot crucifix that hung above the pontiff, who liked it so much that before he went back to the Vatican, he asked to take it with him.

“Not that I’m not passionate about rock ’n’ roll,” Davis says. But the projects he’s most excited to discuss have nothing to do with music: a movable scoreboard for a hockey arena, animatronics for theme parks, augmented-reality body scans to enhance the retail experience.

Automation is at the root of Tait’s strategy for the future. Navigator, its proprietary software, drives 80 percent of its projects. Computer-controlled tools do the work that was once the purview of shopworkers. “Things have advanced so much,” says Russell Snavely. “I probably didn’t adapt well enough.” On the manufacturing floor, he wears a hat that says “Older Than Dirt.” If a CNC machine can’t make something, Snavely’s called in to do it by hand. He’s the company’s longest-tenured employee. “In all honesty,” he says, “I feel like a dinosaur.”

As Davis sees it, nothing about the core mission of any of the other companies that make up Rock Lititz has changed. It’s just gotten bigger. “I’ve gotten so used to growth that I don’t think of it as growth anymore,” he says. Last year, he brought on a private-equity firm to facilitate Tait’s ambitions. “The basis for our whole business is creating these magic moments. What that means is more spectacle.” Is there such a thing as too much spectacle?

“Gosh, I hope we never find it,” he says. “Think about what the Romans did. They would flood the venue; they would have tigers fighting humans. Real tigers! Human beings crave the spectacle.”

Michael Tait recently sold his stake in Rock Lititz, leaving Troy Clair and Davis as primary owners. “This is making money, but this is land, and we’re developers, and the real payoff comes down the line,” Tait says one afternoon, seated in a common area of Pod 2. “It’s a long-term investment, and I ain’t going to be here long-term.”

Tait is seventy-four. His bald head is ringed by long, white hair, irregularly dyed blue. His eyebrows, too. He wears mismatched shoes. He likes attention. (“Of course I do. Who doesn’t?”) At least he’s self-aware. “I just got a little crazy in the last few years,” he says. His biggest retirement project is also his newest: Mickey’s Black Box, the community theater he is planning as part of Rock Lititz’s expansion. “One of the beauties of my situation,” he says, “is that I can afford to build this building without borrowing.” All in, he’ll pay around $5 million, cash. The idea came to him last spring, after reading in the local paper about a one-woman show whose star had terminal ovarian cancer. Tait knew her. Her name was Camilla Schade, and she’d once had a troupe to which Tait would donate materials. He didn’t see her show, and she died shortly after. “I love Lititz. I love Lancaster County. I just thought this would be something that’s good for the community,” he says. “I mean, obviously, I believe in Tait, Clair, and employment, blah, blah, blah. That’s all good. But this is going to foster the arts that are not looked after.”

How he’ll use the space—“well, that’s a mystery.” He plans to offer it to artistic endeavors for little more than the electricity costs, but he’s not above renting it out for a wedding at full market rate. It’s unlikely that he’ll return to the type of work he left behind when he ceded Tait Towers to the next generation. “If I was twenty, I probably wouldn’t do the rock ’n’ roll thing,” he says. “Everyone wants a bigger show than the next person. It’s like a three-ring circus. I never did this for the money. I did this because I wanted to build cool shit.”

When Gary Ferenchak is alone at the Studio on a windy day, the building creaks and groans as if it were about to come down. It won’t. If a westward wind were to whip around Zion Hill and hit the Studio at one hundred miles per hour, the building would sway nine inches, but it would endure. Still, the big space at times seems to create its own climate, and at other times to respire.

Tied to one corner of the catwalk is an inflatable eyeball, a two-year-old remnant from the rehearsals for Katy Perry’s Witness tour.

Out on the floodplain, ducks congregate year-round, sometimes with herons. In the winter, snow geese fly over by the thousands. The only long-stay residents on the property are an Amish family: the brother of the man on the next farm over, his wife, and their young children. They live and work on the northwest corner of the land, in a cluster of old structures that includes a 19th-century farmhouse, a banked barn, and a concrete hatchery. When the family moved in, Rock Lititz helped out, covering the cost of dumpsters and repairs to the roof of the barn. In return, the family is expected to keep their small section of the property looking presentable.

Last year’s corn crop grew on the future site of Mickey’s Black Box.

It’s early March. A week ago, Ferenchak loaded out Billie Eilish’s crew. Before that was Hall & Oates, and before that, Green Day. (Rock Lititz wouldn’t confirm the Studio’s schedule, citing the confidentiality of its clients.)

The BTS load-in has begun. They’ve just finished assembling the steel framework onto which the stage will be constructed. (Stadiums don’t have ceilings, so you bring your own.) The plan to drop off thirty shipping containers was nixed. Instead, the components arrived on fifty-three-foot flatbeds, at least a dozen of them. They drove right into the Studio.

Due to the coronavirus outbreak, the band has canceled the first leg of the tour, a four-night run in Seoul. But tomorrow morning, the band’s production team will arrive as planned. Semitrucks will show up, transporting a city-block-sized video screen that Tait built, a sound system from Clair Global, and all the rest of it. Eighty-five local crew members will be on hand. Andrea Shirk has asked them to gather early, to review best sanitary practices.

It will be a busy day.

Ferenchak climbs into the CrossRoads Zinger. The space is spare, but he likes it that way. This isn’t home, after all. He stretches out on the cream couch, in the starboard slide-out. Black sheets on the windows block the glow of the parking-lot lights. It’s the night shift on the floodplain. When the air is still, it sounds like a frog convention.