BTS and EXO: The soft power roots of K-pop

Alamy

AlamyThe wave of South Korean pop culture around the world hasn’t happened by accident – it was a deliberate government plan, writes Christine Ro. And it has even reached North Korea.

GeumHyok Kim loves South Korean dramas, especially historical shows like Dae Jang Geum (Jewel in the Palace). He used to watch them every day, and would also repeatedly watch music videos of South Korean pop groups like Girls’ Generation. What’s unusual about Kim’s love of such culture is that it is illegal. Kim is from Pyongyang, North Korea, where a person caught accessing or smuggling foreign media can be sentenced to a stint in a labour re-education camp or, in the most severe cases, public execution. While extreme, Kim’s experiences show the truly global spread of South Korean culture.

More like this:

In just a few decades, South Korean culture has taken the world by storm. Since the country’s democratisation in the late 1980s, the relaxation of censorship, the reduction of travel restrictions, and the push to diversify the economy have all contributed to the global spread of its culture. This hasn’t occurred by accident. Hallyu, or the ‘Korean wave’ of culture, has been a deliberate tool of soft power. South Korea isn’t alone in this; many countries invest in cultural councils and exchanges partly to strengthen diplomatic aims. But the South Korean government’s push for cultural power has had remarkably quick success.

Alamy

AlamyThe roots of Korean participation in modern pop culture can be traced back decades. For instance, in 1959, the Kim Sisters, a singing trio, arrived in Las Vegas for the first of many performances. This group, who appeared 22 times on The Ed Sullivan Show, have been called “cultural ambassadors” and “America’s original K-pop stars”.

But hallyu, or the Korean wave, only kicked off following the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. According to a new book, South Korean Popular Culture and North Korea, South Korea’s government “targeted the export of popular media culture as a new economic initiative, one of the major sources of foreign revenue vital for the country’s economic survival and advancement”. In 1998, President Kim Dae-jung, who called himself the “President of Culture”, was inaugurated. His administration started to loosen the ban on cultural products imported from Japan, which had been a reaction to the Japanese colonisation of Korea in the first half of the 20th Century; first manga was allowed back in. The following year, the government introduced the Basic Law for Cultural Industry Promotion and allocated $148.5 million (£113 million) to this.

In music, South Korean pop groups had flourished domestically in the early 1990s. Seo Taiji & Boys debuted on a Korean talent show in 1992, marking the start of modern K-pop, with its integration of English lyrics, hip hop elements, and dance. By the mid-90s, the K-pop star system had become entrenched in South Korea.

Yet the government wanted to spread their culture around the world – and it started in an unlikely place. South Korea’s first major global successes were soapy TV programmes known as K-dramas, initially intended for domestic audiences, but which found popularity in other parts of Asia and further afield. 2002’s Winter Sonata became a global phenomenon partly through the South Korean government’s deals with broadcasters in strategic locations, like Iraq and Egypt, to increase positive feelings towards Korea.

Alamy

AlamyThe international success of K-dramas spurred a careful planning of the globalisation of K-pop, beyond the groups that had achieved national fame. As with the electronics and automobile industries, the centralisation of economic power within large conglomerates allowed for slick production under careful discipline. In the K-pop star system, this meant recruiting pop musicians and managing them through years of training and careful presentation – which paid off with dizzyingly successful pop acts like the boy band EXO, who made their television debut in 2011. EXO was conceived of as a South Korean-Chinese group, performing in both Korean and Mandarin and promoting their songs in both countries.

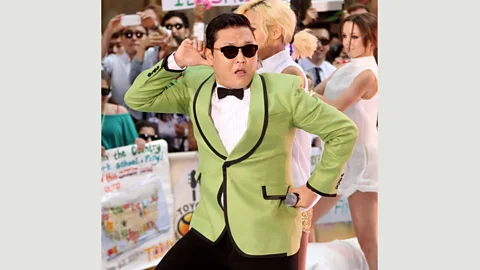

One year later, the music video for Psy’s Gangnam Style became the first YouTube video to achieve 1 billion views (and started a global craze for mock-horse-dancing). UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, praising the song, described the arts as a path to cultural understanding.

Alamy

AlamyAccording to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry’s Global Artist Chart, South Korean boy-band BTS were the second best-selling artists of 2018 worldwide, and the only non-English speaking artist to enter the chart. As of 2019, the group accounted for $4.65 billion (£3.5 billion) of South Korea’s GDP – and they became the first Asian band to surpass 5 billion streams on Spotify. The country has seen success in film, too: this year, Bong Joon-ho’s dark comedy Parasite became the first film not in English to win the best picture Oscar, and so far it has grossed more than $50 million (£38 million) at the US box office.

The popularity of Korean music, TV and films has spurred growth in other sectors, such as tourism, food and language education. Exports of cosmetics and skincare products, a fixture in beauty-obsessed South Korea, have also skyrocketed. In 2015, South Korea exported cosmetics with a total value of $2.64bn (£1.85bn). And in 2017, South Korean President Moon Jae-In announced the aim of spreading Korean film, music and TV to 100 million people within five years.

But how has the international diffusion of South Korean culture played out in its very different neighbour to the north?

From South Korean wave to Southern wind

Sunny Yoon, a media professor at Seoul’s Hanyang University, emphasises that North Korean audiences aren’t ignorant and passive consumers of foreign cultural products. But as North Koreans who watch South Korean media are, according to Professor Yoon, “in desperate situations (extreme poverty and no freedom)… it is natural for them to desire a new way of life by watching foreign media”.

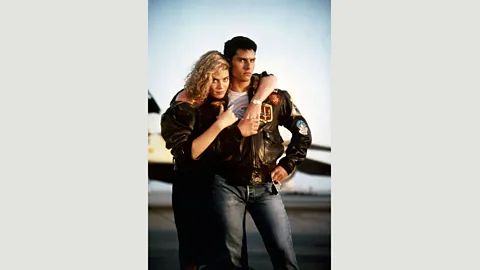

Hallyu has been called a ‘cultural weapon’ in North Korea, where it is referred to as nampung (‘Southern wind’). Given the secrecy in the Hermit Kingdom, what is known about South Korean culture in the North comes mainly from people who have fled North Korea. One is GeumHyok Kim, who as a member of the elite class had certain privileges that allowed him to access foreign culture. At his college, where he was studying for an English degree, his professors would show Hollywood films in their classes: big-budget fare like Top Gun and Armageddon.

Alamy

AlamyKim would give South Korean dramas to his friends, which occasionally landed him in trouble. He was interrogated twice as a 15-year-old about possession of foreign media. He avoided punishment because his father bribed the officials. “Culture makes people brave,” he reflects now. It also makes them curious about differences between their countries and others, as in North Korea. “They started to not believe what the government says.”

And, importantly, Kim was allowed to study in Beijing. Being around classmates from different countries, who exposed him to documentaries and books about North Korea, was a shock. “It really made a big bang in my brain,” he says. “I realised that what I knew about North Korea was all a lie.” Eventually he made the difficult decision to defect, although it meant cutting himself off from his family and putting them at risk.

Black-market access like Kim’s has been key to the penetration of South Korean and Western media in North Korea. The catastrophic North Korean famine in the mid-1990s, when Kim was a child, reduced citizens’ trust and reliance on the government. Desperate people turned to smuggling for the food they needed, and sophisticated international networks increasingly brought in items that North Koreans could sell to make a living. This includes USB drives containing South Korean films or TV dramas, whose sale can bring in over a month’s worth of food.

Alamy

AlamyAs North Korea is pursuing a close relationship with China, being caught with Chinese films is less serious than, for instance, being caught with the songs of BTS. Yet watching foreign media is widespread. Some North Korean fans watch programmes with the blinds drawn or one earphone on low volume, keeping an ear out for inspectors.

This is aided by the spread of certain technologies. Rich families have solar panels, due to frequent power outages, that allow them to enjoy foreign media uninterrupted. A lucky minority have mobile phones. While the North Korean regime jams foreign broadcasts, some make it through, especially in border areas. And USB drives have become increasingly popular in North Korea, for being easier to smuggle than previous digital media like DVDs.

The influence has had some surprising effects, for instance on language. North Koreans exposed to South Korean pop culture have adopted slang and accents from South Korean actors. Some wedding ceremonies have two parts: one with songs approved by the North Korean government, and the second one secretly incorporating rituals borrowed from South Korean media. South Korean makeup and fashion are popular in North Korea, whose regime restricts hairstyles and clothing. This seems to be loosening recently, though, partly due to the influence of fashion-loving Lee Seol-Ju, Kim Jong-Un’s wife.

Pop culture opening minds

Certain Western pop culture is popular as well. As well as K-pop, defectors claim that films such as Titanic and bands like Westlife made them increasingly aware of what the North Korean regime wasn’t telling them. Access to foreign culture appears to affect loyalty to North Korea. Almost all recent North Korean refugees report being influenced by South Korean TV, films or music.

They can be disillusioned on arriving in the South, seeing that not everyone is wealthy and trouble-free. The very different gender norms also take some getting used to. There have been challenges for North Koreans integrating into South Korea: the national suicide rate – already high – is three times higher among defectors. Some choose to return to North Korea.

The influence of culture is ultimately limited. North Koreans’ enjoyment of foreign media “demonstrates political dissatisfaction, but this does not turn into an overt political resistance”, says Yoon. Songs, comics, TV programmes and films expand ideas, but on their own won’t bring about regime change.

As Kim says, “in dramas, in movies, we can see other societies that are very different. But there is a limit. No one is telling about democracy in dramas. They always tell about love.” Yet they still have an important role. “Culture is soft, culture is light, but culture has power to distribute information to people,” emphasises Kim, who’s now studying politics and international relations in Seoul. “I believe in the power of culture.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.