In Danny Boyle’s new movie, Yesterday, a failed indie rocker (Himesh Patel) gets hit by a bus and wakes up in an alternate reality where nobody but him remembers the Beatles, so he plagiarizes “She Loves You,” “Hey Jude,” and other Lennon-McCartney standards and unseats Ed Sheeran as the world’s biggest pop star. The film, written by Richard Curtis, is obviously fictional. But 55 years ago, a similar thing, or at least pretty similar thing—minus the bus accident and the interdimensional copyright infringement—really happened to Peter Asher.

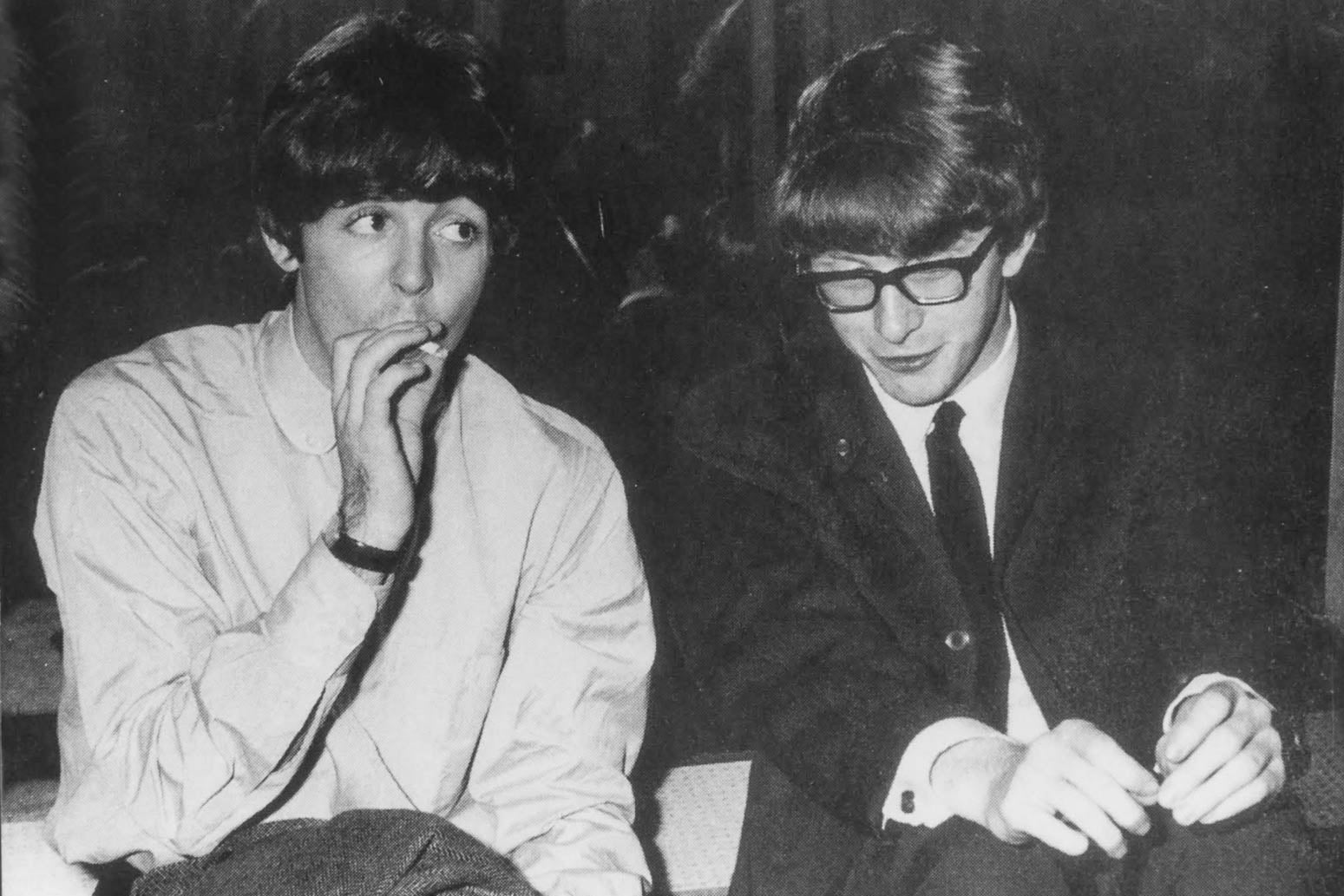

On Feb. 28, 1964, British folk duo Peter and Gordon released their debut single, “A World Without Love.” It didn’t matter that the song was an adequately harmonized, extremely melodramatic ballad about doomed teenage romance. (“Please lock me away,” it starts, “and don’t allow the day here inside, where I hide with my loneliness.”) It didn’t matter that neither Asher nor his performing partner, Gordon Waller, 20 and 19 at the time, were natural heartthrobs; indeed, Asher’s glasses, haircut, and teeth would later give Mike Myers the visual inspiration for Austin Powers. All that mattered at that precise instant in history was that “A World Without Love” was written for Peter and Gordon by Paul McCartney (and credited to Lennon-McCartney, like all of McCartney and John Lennon’s songs were then, no matter who wrote what) and therefore infused with the magic of the Beatles, which meant Peter and Gordon had been handed musical plutonium.

“It’s interesting that Yesterday reminded you of us. I hadn’t made that connection, but I haven’t seen it yet,” says Asher, now 75, calling from his home in L.A. last week. “I think we were Beatles substitutes for some people. They’d think, I can’t get to a Beatles gig, but I can get to a Peter and Gordon gig, and that’ll have to do for now.”

That sounds modest, but in the spring of 1964, the demand for Beatles substitutes was through the roof. The Beatles themselves had come to New York and performed on The Ed Sullivan Show for three consecutive Sundays that February, but then disappeared for most of March and April to shoot A Hard Day’s Night. Panting Americans sent a dozen Beatles songs onto the Billboard Hot 100 chart, and during the second week of April, the band occupied the entire top five, a feat no artist has managed since. In that fevered moment, a new Paul McCartney song landed like an atom bomb. “ ‘A World Without Love’ went to No. 1 in the U.K., and then Europe, and then the U.S.,” remembers Asher. In Britain, the song bumped the Beatles’ own “Can’t Buy Me Love” out of the top position—or, says Asher, “ ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ was No. 1 for a gazillion weeks and finally slid down and left us there.”

How did two very regular guys wind up in possession of an original, unrecorded McCartney song in the first place? It helped that McCartney had been dating Asher’s younger sister Jane. It especially helped that, in December 1963, McCartney moved out of the flat he shared with John, George, and Ringo and into the Asher family’s West London town house at 57 Wimpole St., taking the top-floor guest bedroom down the hall from Peter’s.

By this point, McCartney, then 21, was already one of the most famous people alive, but the Ashers weren’t slouches. Peter, Jane, and their younger sister Claire had all been child actors and starred in movies and TV shows. Peter’s father, Richard, was a prominent psychiatrist who discovered Munchausen syndrome. Peter’s mother, Margaret, was a professor of music and had coincidentally given oboe lessons to Beatles producer George Martin.

McCartney lived with the Ashers rent-free, but he probably boosted the value of their house (which is now a wellness spa) by writing “And I Love Her,” “Every Little Thing,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “I’ve Just Seen a Face,” “You Won’t See Me,” and “I’m Looking Through You” on the piano in Margaret’s basement music room. One day, Lennon came over for a writing session. “I remember Paul calling up the stairs, and then me going down to the music room,” says Asher. “He and John had just written ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ side by side on the piano bench, no guitars. I sat on the sofa and they played it for me. I was the first person to hear it.” Unfortunately, Asher was on tour with Waller the morning McCartney woke up having written “Yesterday” in his sleep. “My mother was the first to hear that song,” Asher says. “He was playing it to people and asking what it was, not realizing he’d written it.”

Was having to share a bathroom with the greatest pop songwriter of the 20th century ever hard on Asher’s ego? “It was clearly evident that Paul could play guitar and write songs better than me,” says Asher, “but he was also better than everybody else! I don’t remember feeling deprived or insulted or jealous about how good he was. I just remember feeling a sense of awe. I wasn’t Salieri—although I did just read that Salieri is undergoing a reappraisal these days.”

Asher and Waller had recently graduated from coffeehouses performing Everly Brothers–style versions of traditional songs like “500 Miles.” “When [EMI A&R manager] Norman Newell signed us, he liked the vocal blend and thought we might be Britain’s response to the folk boom,” says Asher. “Maybe we were Peter and Paul without Mary.” Newell booked them a recording session for Jan. 21, 1964, and asked if they had any other songs beyond the ones on their demo that they wanted to take a crack at. Did they ever! “I’d heard Paul play ‘A World Without Love’ around the house and I liked it,” says Asher. “When we had the record deal, I said, ‘We’re looking for extra songs. Could I give that one a try?’ ”

McCartney wrote “A World Without Love,” or at least most of it, when he was 16. By anybody else’s standards it would be considered a perfect pop song, but on the scale of his own work it was just OK, more of a “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” than a “Penny Lane.” Lennon vetoed it for the Beatles. “John didn’t think much of the song, so Paul hadn’t even finished it apart from the two verses,” says Asher. “I remember having to ask him a couple of times to finish it. Finally, he did it on the spot. He took his guitar into his room for an annoyingly short seven or eight minutes, and then came out with the bridge, which was perfect.”

When Peter and Gordon got to the studio, “I don’t remember anyone going, ‘Oh my God, this is a masterpiece,’ ” says Asher. “It was more like, ‘Let’s figure out the chords and get it done before we go into overtime.’ ” Asher and Waller sang, and Asher helped with the arrangement, but the instrumental track was left to session musicians, including guitarist Vic Flick. “He was also famous for being the guitarist who played the James Bond lick,” says Asher. “So this was his twin claim to fame.” (Flick’s flashy call-and-answer exchange with the organ near the song’s end became a minor liability in TV performances, during which Asher and Waller were left awkwardly strumming their acoustic guitars for 20 seconds while an unseen Flick shredded on the prerecorded backing track. “Neither of us were good enough guitar players to [mime] the Vic Flick part,” says Asher.)

The song’s success “immediately turned my life upside down,” says Asher, who’d been studying philosophy at King’s College. “I had to go see my tutor and explain to him that this odd thing had happened: We’d made a No. 1 record and they were very anxious for us to come to America.”

Peter and Gordon became only the second British Invasion act after the Beatles to have a No. 1 hit in the U.S., and so they played concerts to some of the horniest and least decorous teenagers our nation has ever produced. “People in America knew how they were supposed to act, the screaming and hair-tearing and all that,” says Asher. “The strangest thing that happened was at an outdoor gig, at a show where the stage was on a truck bed. The crowd overcame security and was racing toward us. [The police] made us run to the exit, and as I jumped off the stage, my glasses fell down on the lawn, so I picked them up and kept going. But as I looked back, this girl had knelt down to where my glasses had fallen, and she was pulling up the grass and eating it. I thought, well, that’s weird.”

When Asher and Waller got back to London, McCartney already had their follow-up single waiting. “Paul had written ‘Nobody I Know’ for us—with a bridge, all ready to go, no begging involved,” says Asher. “People always ask us how we got so many songs out of Paul McCartney, but the answer was, he was just following the rules of songwriting. If you write a huge hit for an act, you want to write the follow-up. You don’t want somebody else selling records on your coattails.”

Later, McCartney wrote “I Don’t Want to See You Again” and “Woman” for Peter and Gordon, and they also had hits with Del Shannon’s “I Go to Pieces,” Buddy Holly’s “True Love Ways,” and “Lady Godiva,” by Mike Leander and Charlie and Gordon Mills. “We always managed to find another good song in the nick of time,” says Asher. “I guess that’s how we ended up with seven or eight hits in a row.” (Peter and Gordon also wrote plenty of songs themselves, including the B-sides to most of their singles. “We wanted to put our songs on our singles as a matter of pride, quite apart from the theoretical extra money,” says Asher, “which turned out to be very theoretical, like most money back in that era.”)

In 1966, both McCartney and Asher moved out of the house on Wimpole Street, “me to a modest flat I rented not far away,” says Asher, “and Paul to his Beatle mansion on Cavendish Avenue, which he still has.” Two years later, following a lukewarm reception for their Sgt. Pepper–influenced psychedelic album, Hot Cold & Custard—which is way better than that sounds—Peter and Gordon split up. Waller released a solo album and Asher became the head of A&R for the Beatles’ Apple Records, where he signed James Taylor and eventually found his real calling as a producer for Taylor, Linda Ronstadt, Bonnie Raitt, Cher, 10,000 Maniacs, Neil Diamond, and lots of others. Asher and Waller reunited in 2005 and performed together until Waller’s death from a heart attack in 2009. These days, Asher hosts a weekly show, From Me to You, on the Beatles SiriusXM station and occasionally tours as a duo with Jeremy Clyde, formerly of the group Chad & Jeremy. (Clyde’s partner, Chad Stuart, retired last year).

The Peter and Gordon catalog is mostly available for streaming, but don’t look for it on CD or vinyl. “I have less than no say on those matters,” says Asher. “I’ve been overseeing the major remastering project for all the James Taylor Warner Bros. albums, because there’s always a market for James, but if I said, ‘Let’s do a major vinyl remastering of the Peter and Gordon catalog, and Hot Cold & Custard, the great undiscovered semi-psychedelic masterpiece,’ I would probably be laughed out of the office.”

Still, though, being Peter and Gordon sounds a lot more fun than however you spent your early 20s. “At first, America didn’t quite understand the whole Beatles thing, and ‘Beatle’ became a generic term for anyone with similar suits and haircuts,” Asher says. “I remember being in an elevator with Gordon somewhere in America, and some kid asked, ‘Are you a Beatle?’ And I said, ‘No, they’re a different band.’ But what he was really asking was, ‘Are you part of that phenomenon?’ So the answer was, ‘Well, sort of.’ ”