More than ever, we need good journalism to support fact-based debate. But the business of publishing is in crisis. The most recent job cuts—some 2,000 people at the likes of BuzzFeed, Vice, and HuffPost—top off a brutal decade for the news industry. Between 2007 and 2017, the number of full-time journalists in the UK alone fell by 6,000 (pdf).

In March 2018, the UK government tasked veteran journalist Frances Cairncross to explore ways of sustaining high-quality journalism in a fast-changing media landscape. The Cairncross Review published its recommendations this week. (Disclosure: I contributed to the report, as part of an 11-person advisory panel.) These span everything from supporting news publishers through tax breaks to correcting market distortions in the digital advertising market by reining in the big tech platforms.

If adopted in full, the recommendations should provide a means to shore up revenues and stop the bleeding of the news industry, especially that of local press and investigative journalism. But it may not be enough to ensure the industry’s long-term survival. For that, the industry needs a media-literate population that values and incentivizes good journalism.

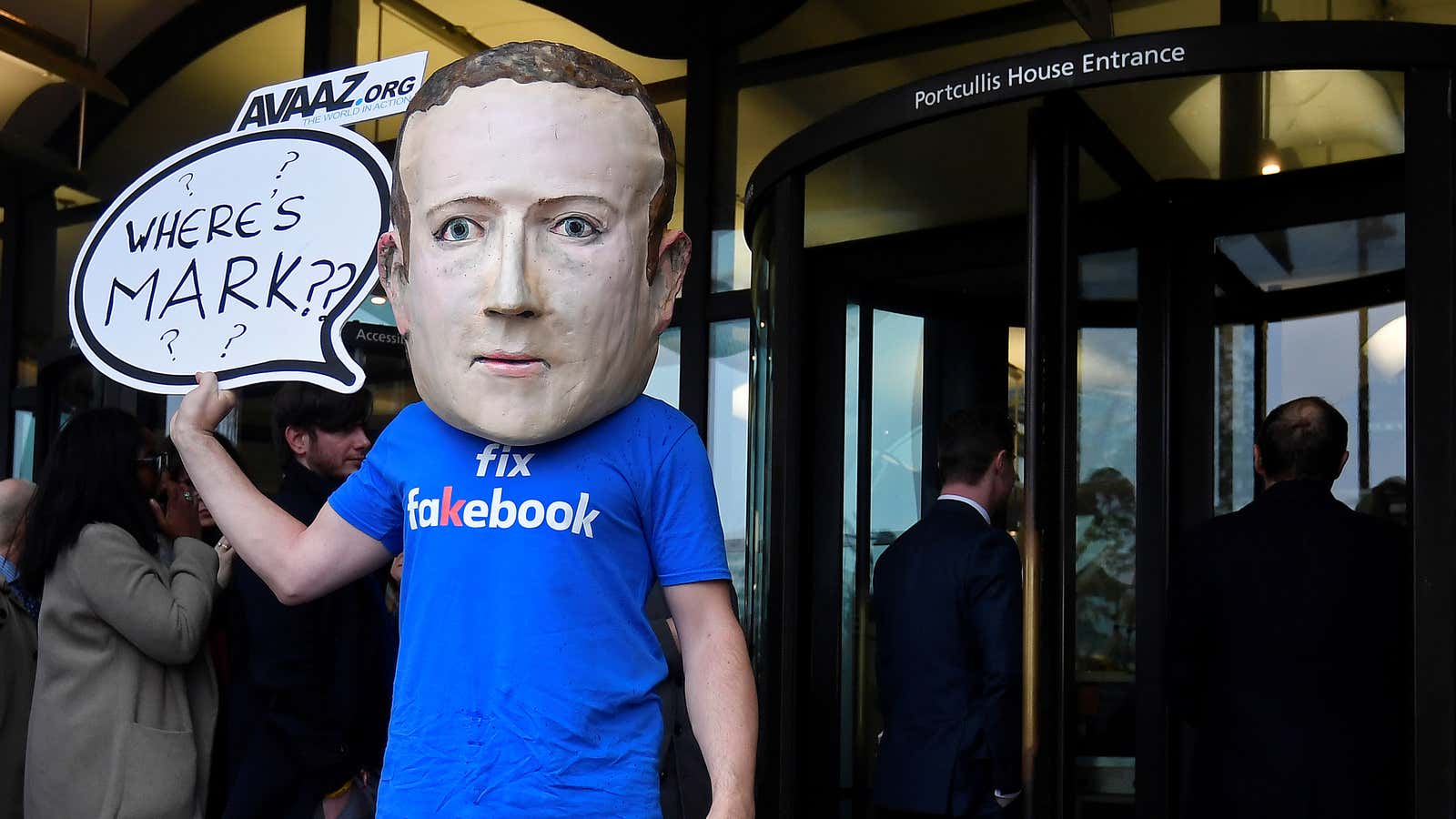

The paltry level of media literacy was on display last year, when lawmakers in the US and Europe questioned executives from Google and Facebook about political advertising on their platforms and the political bias of their own employees. The poorly phrased questions showed the lawmakers’ ignorance about the basics of how a search engine or a social-media site works.

And media literacy is not better among children. A June 2018 report by the National Literacy Trust found that “only 2% of school children in the UK have the critical literacy skills they need to tell if a news story is real or fake.” That’s despite the UK widely being considered as a world leader in media-literacy education. “Media studies” as a subject is available in the school curriculum, but it is not compulsory and only 8% of British high-school students opt for it.

“Media literacy provides a framework to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and participate with messages in a variety of forms,” according to the US-based Center for Media Literacy. In that sense, “media literacy is needed not only to engage with the media but to engage with society through the media,” writes Sonia Livingstone, a professor of social psychology at the London School of Economics, on a university blog (emphasis Livingstone’s).

The fundamentals are simple. Citizens need the basic building blocks of critical thinking: how to judge where information comes from, its purpose, and what the message’s context say about its meaning. These are increasingly important life skills in an always-on media world, and could help readers avoid being influenced by Russian disinformation campaigns, thinly sourced clickbait, or sponsored content masquerading as real news.

Rolling out media-literacy courses across a country’s population, including adults, is not going to be cheap. It’s why government initiatives to raise awareness have in the past come and gone quickly. Any costs associated with raising media literacy, however, are likely to be lower than those borne by a society with a pervasive lack of that knowledge.

The good news is that even small interventions can produce positive results. A 2012 review of 51 studies of media-literacy initiatives conducted over the previous 30 years found that most participants improved their understanding of media across a long list of measures.

The thing is, our attention turns to media literacy only when there is a crisis of some sort. But proficiency in interpreting the news requires sustained effort and a long-term outlook. “Investment in media literacy is paltry and often wasted when it is not part of a joined-up, strategic, long-term approach,” concluded the “Tackling the Information Crisis” report from the London School of Economics published in November 2018.

Two concrete measures could jumpstart the UK’s efforts at increasing media literacy. One comes from the Cairncross Review: Ofcom, the country’s communications regulator, should not just measure the levels of media literacy among the UK public, but should also work alongside platforms and publishers to fund initiatives that improve those skills among adults. Another, which the review did not include, is to ask the Department of Education to make some form of media studies a compulsory part of the school curriculum. And the government should provide guaranteed financial support to both these interventions, for decades to come. (Though these are UK specific recommendations, most rich countries have similar bodies that can be entrusted with taking on the important task.)

To be sure, media literacy isn’t going to solve all the problems facing society. But it’s clear that a more-media literate population will be better at dealing with them. And, in the process, high-quality journalism could, once again, find a sustainable business model.