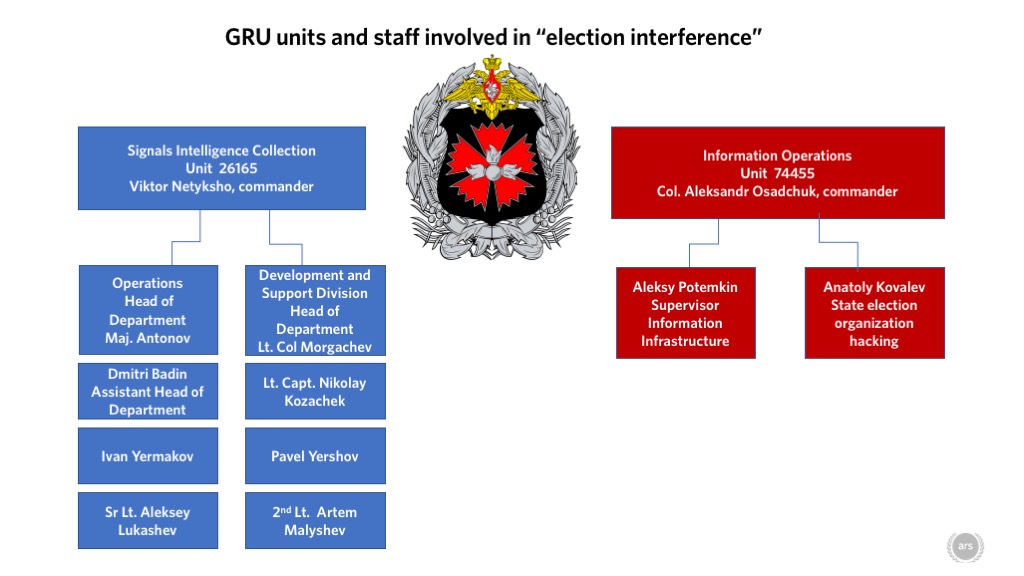

In a press briefing just two weeks ago, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced that the grand jury assembled by Special Counsel Robert Mueller had returned an indictment against 12 officers of Russia's Main Intelligence Directorate of the Russian General Staff (better known as Glavnoye razvedyvatel'noye upravleniye, or GRU). The indictment was for conducting "active cyber operations with the intent of interfering in the 2016 presidential election."

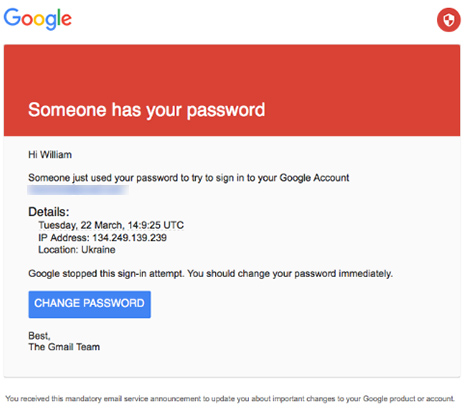

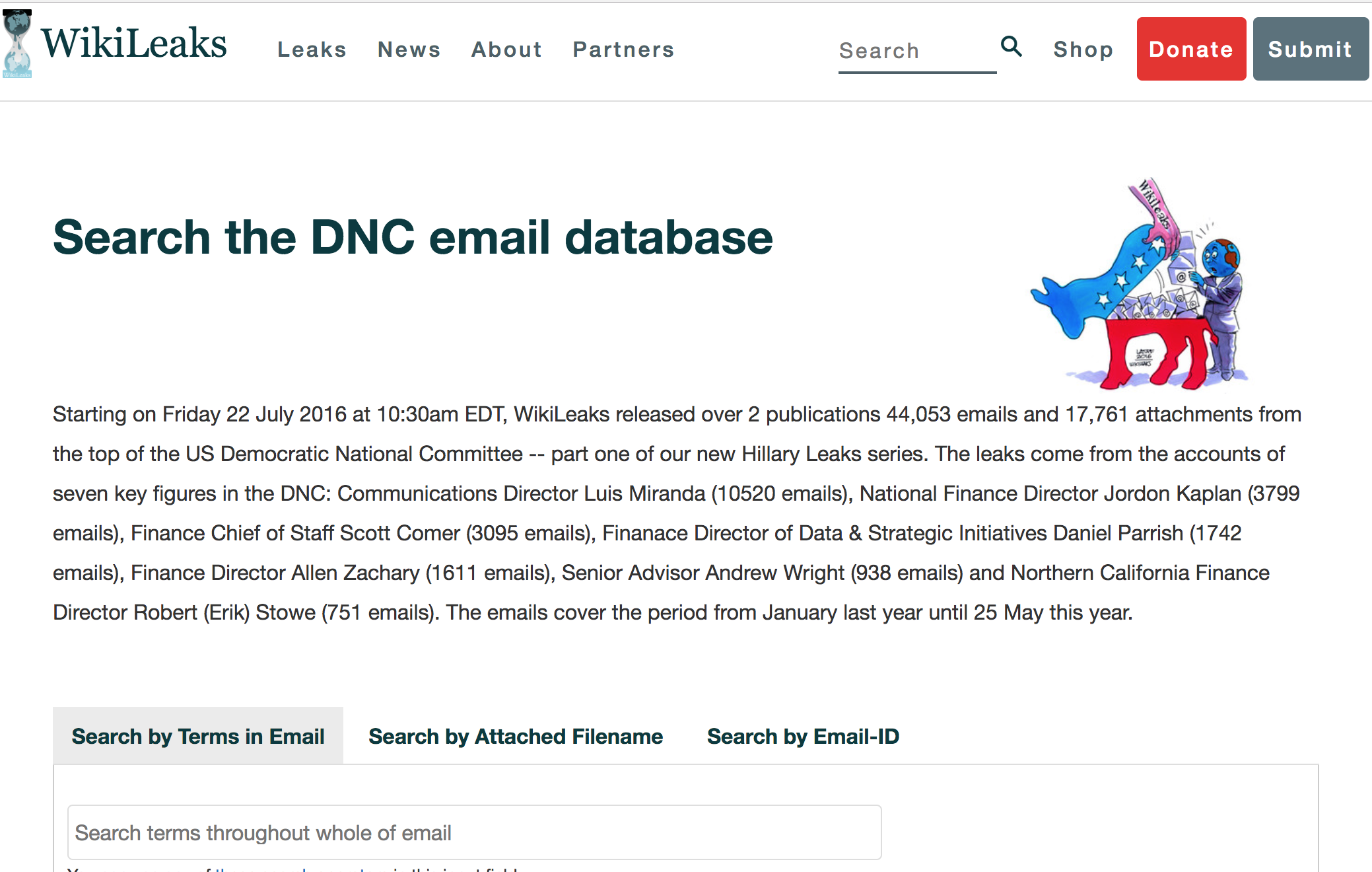

The filing [PDF] spells out the Justice Department's first official, public accounting of the most high-profile information operations against the US presidential election to date. It provides details down to the names of those alleged to be behind the intrusions into the networks of the Democratic National Committee and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the theft of emails of members of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign team, and various efforts to steal voter data and undermine faith in voting systems across multiple states in the run-up to the 2016 election.

The allegations are backed up by data collected from service provider logs, Bitcoin transaction tracing, and additional forensics. The DOJ also relied on information collected by US (and likely foreign) intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Reading between the lines, the indictment reveals that the Mueller team and other US investigators likely gained access to things like Twitter direct messages and hosting company business records and logs, and they obtained or directly monitored email messages associated with the GRU (and possibly WikiLeaks). It also appears that the investigation ultimately had some level of access to internal activities of two GRU offices.

This is the first time that President Donald Trump's Justice Department has filed official charges against members of a Russian government agency for taking actions intended to influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential campaign—though Rosenstein was careful to assert that there was no allegation that votes were changed by this operation. The indictment details match up with much of what we've already learned about the information operations campaign run by the GRU. But the new findings went further, comfortably identifying each person behind the various elements of the campaign, from the first spear phish to the final data theft.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...